Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go. Three years ago I was giving a workshop in the Rockies. A student came in bearing a quote from what she said was the pre-Socratic philosopher Meno. It read, “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?” I copied it down, and it has stayed with me since.

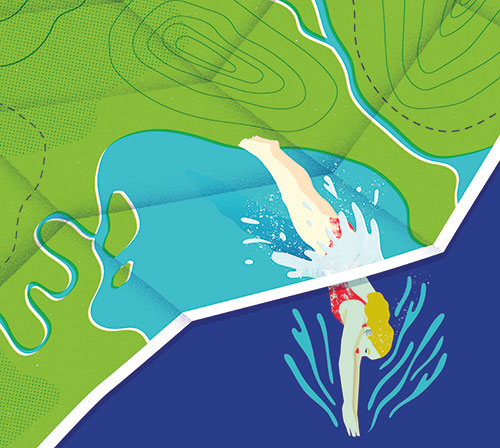

The student made big transparent photographs of swimmers underwater and hung them from the ceiling with the light shining through them, so that to walk among them was to have the shadows of swimmers travel across your body in a space that itself came to seem aquatic and mysterious.

The question she carried struck me as the basic tactical question in life. The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation. Love, wisdom, grace, inspiration – how do you go about finding these things that are in some ways about extending the boundaries of the self into unknown territory, about becoming someone else?

The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know what is on the other side of that transformation

Certainly for artists of all stripes, the unknown, the idea or the form or the tale that has not yet arrived, is what must be found. It is the job of artists to open doors and invite in prophesies, the unknown, the unfamiliar; it’s where their work comes from, although its arrival signals the beginning of the long disciplined process of making it their own. Scientists too, as J Robert Oppenheimer once remarked, “live always at the ‘edge of mystery’ – the boundary of the unknown”. But they transform the unknown into the known, haul it in like fishermen; artists get you out into that dark sea.

Edgar Allan Poe declared: “All experience, in matters of philosophical discovery, teaches us that, in such discovery, it is the unforeseen upon which we must calculate most largely.” Poe is consciously juxtaposing the word “calculate”, which implies a cold counting up of the facts or measurements, with “the unforeseen”, that which cannot be measured or counted, only anticipated. How do you calculate upon the unforeseen?

It seems to be an art of recognising the role of the unforeseen, of keeping your balance amid surprises, of collaborating with chance, of recognising that there are some essential mysteries in the world, and thereby a limit to plan and control. To calculate on the unforeseen is perhaps exactly the paradoxical operation that life most requires of us.