But then, the Taliban arrived. Everything collapsed overnight.

Her studies were swapped for hard labour, her bright clothing with a black veil covering her body head-to-toe.

Her future, her face, all disappeared.

“I could not believe that from now on, I have to stay home and weave carpet and do housework. With all the dreams that I had, I was captured in a prison with no way out,” says Diba.

With the takeover of the Taliban in Afghanistan, Diba was deprived of her basic rights as a human being. She has been banned from going to parks or any other public places unless a close male relative is with her. She has been banned from working outside the home. And like all females, she has been banned from studying.

Now, Diba has two choices: she can stay home and knot her dreams to the threads of a carpet she is weaving, or risk her life by going to an underground school.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

With the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul on 15 August, 2021, history repeated its dark side for Afghan women. The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan has once again issued numerous orders for the systematic exclusion of Afghan women from society, including bans on speaking loudly or laughing in public, wearing high heels, displaying women’s names and photos in public, as well as their participation in radio or TV programs and various job sectors.

They also banned girls from going to universities and, later, prevented them from attending secondary schools.

And so many women went back to what they had done 25 years ago – creating underground schools. Since 1996, the first takeover of the Taliban, Afghan women have invented a form of defiance against the Taliban by continuing their education in secret schools. Underground schools are hidden places inside homes that are run mainly with the help of trusted volunteer teachers and families despite the threats to their lives.

Teachers and students attending underground schools face likely punishments such as imprisonment or, worse, whipping and beating. With rumours of executions for girls who study, it’s little surprise all of those interviewed refused to be pictured and asked for their names to be changed.

In a poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of Kabul, Ershad, a teacher and a researcher in sociology, discovered 10 schoolgirls, and among them was Diba. They all gathered in a home to share their stories with Ershad. The girls had been banned from attending schools and universities. Instead, they were forced to weave carpets from morning till evening at home every day, earning 2,000 Afghanis – about $10 a month.

Many were left feeling depressed and hopeless.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Some even tried to take their own lives.

“I just wanted to document their stories and maybe write about them one day. But when I saw their tears, I asked them what can I do for you? And they answered that they want to learn English,” says Ershad.

He tried to find a sponsor for the girls and introduced them to an English teacher. He himself started teaching them life skills, and his wife also agreed to teach maths. Gradually, the number of their students increased, and he thought of creating a secret school. Without any budget, he raised money with the support of his trusted Afghan and Iranian friends, rented a room, and called it ShiftLand, “The inspiring land of shifting and enlightenment.”

The ShiftLand teachers, mostly Iranian, are all volunteers, teaching the girls online from the UK, Germany, India, and Iran. Children’s literature, philosophy for children and English are the main topics of the school. Also, an Iranian psychologist provides online individual consultations to the girls voluntarily, helping them to cope with their difficulties.

The students’ age group varies, ranging from seven years old, with the majority of the girls in secondary school and above. Some adult students even take on the role of teaching younger ones.

Now, 300 Afghan girls are studying in this secret school under the rule of the Taliban, with 40 of them studying English to pass language tests next year and apply for scholarships.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“We are working hard at a fast pace, and we are optimistic. Everybody knows about Afghanistan’s sorrows and miseries, but nobody knows these girls are the hopes and healings of this country,” says Ershad.

Now, Diba is one of the students who is preparing for the English test and looking for scholarships to save her destiny from the hands of the Taliban. She also teaches English to younger students voluntarily at school. The school has become a happy shelter for the girls and has given them a second life to continue.

“When I entered the place for the first time and saw the girls, I felt that I was alive again. I was very happy to see there are still some people who have not forgotten us, who still care for us, and who haven’t accepted the fact that we must sit at home. I was glad that we were not alone,” says Diba.

“Being among the girls and studying with them motivates me. If we don’t confine ourselves from within, nobody can confine us from the outside. We are a chain of people here who help each other to survive the misery the Taliban has caused us.”

Change a Big Issue vendor’s life this winter by purchasing a Winter Support Kit. You’ll receive four copies of the magazine and create a brighter future for our vendors

Yashar Miremadi is one of the Iranian teachers who teaches girls English online from Manchester. Back in Iran, he had many Afghan immigrant friends with whom he’d shared many good memories. When the Taliban took over Afghanistan and the girls were banned from education, one of his Afghan friends reached out to him to teach the girls English voluntarily.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“The second takeover of the Taliban in Afghanistan and the denial of education to Afghan girls are international issues and require a universal solution. My dream is to see a world where no girls are deprived of education. I hope for that day,” says Yashar, who moved to the UK to study a PhD in Islamic studies.

He describes the girls as very talented and motivated. Many of them had ‘A’ grades in the pre-Taliban period. Yashar is surprised by their excellent command of English despite all the traditional and financial barriers they had in learning the language.

“At first, I held the class in Farsi and English, but at some point, they wanted it to be all in English. They even helped me be a better teacher,” he says.

He meets his 40 students for only one hour a week. The class duration is kept short to ensure the safety of the girls, as it may be dangerous for them to stay in school for long hours. He sends the class materials through PDFs, and the girls open them on their mobile phones, with some using their parents’ phones.

The girls are so high-spirited and cheerful during Yashar’s class that nobody would believe they are living under the brutal laws of the Taliban.

“One day, they were all wearing colourful clothes because of the birthday of the prophet Muhammad. I asked why they didn’t wear these clothes all the time. I was just joking with them by asking this question, but they told me that the Taliban do not allow them to wear colourful clothes,” he says.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Holding an online class in Afghanistan presents many challenges. Unreliable electricity and lack of access to stable internet have caused lessons to be cancelled.

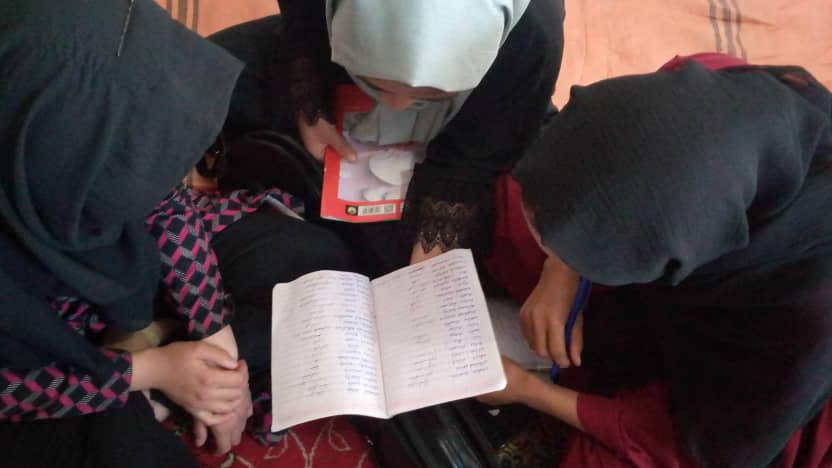

“They all gather in one room to connect to the class. They don’t have access to the Internet separately since it’s too expensive or their families disagree,” says Yashar.

“One day, they asked me to start the class earlier because they couldn’t stay outside in the dark. The Taliban had banned them.”

Attending a secret school under the rule of the Taliban is not the same as any normal school. Every day, Afghan girls risk their lives for another day of studying in the school.

“We always expect the Taliban to come. We don’t know what will happen to those of us who are teaching and studying secretly without their permission. We always live with terror and fear under the rule of the Taliban.

“We have to be careful not to be the centre of the attention of others when we are going to school. We have to hide our books and notebooks,” says Diba

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Even before 2021, Afghan girls were suffering from the inhumane actions of the Taliban, with many experiencing horrifying scenes of suicide bombing in their schools.

“It was two months before the occupation of the Taliban that a suicide bomber attacked our school. More than 90 girls, including my classmates and my friends, died. That day was never wiped from my memory,” says Diba, while her voice is shaking.

“We all came out of our homes with one goal, to study, but when the school day was over, and some of us had come out of school, in one moment, everything went into the air with an explosion,” she continues.

The Taliban ruled the country from 1996 to 2001 – an era which was a mutual nightmare for Afghan women. With the invasion of American forces and the overthrowing of the Taliban in 2001, a spark of hope emerged among Afghan women.

They started to heal their wounded souls by advocating for their rights under the governance of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, returning to universities and taking on various social roles.

But in September 2021, after the withdrawal of the US and NATO forces from Afghanistan and the collapse of the Republic government, 20 years of efforts of Afghan women were erased at a glance.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

With all the hardships and suffering, Afghan girls like Diba have not given up on their dreams. They are determined to reach their mutual goal – freedom.

“I wish for Afghan women to live freely, for themselves, not for others, like true human beings. Women must have the right to decide, study, and live freely,” says Diba.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? We want to hear from you. Get in touch and tell us more.

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription