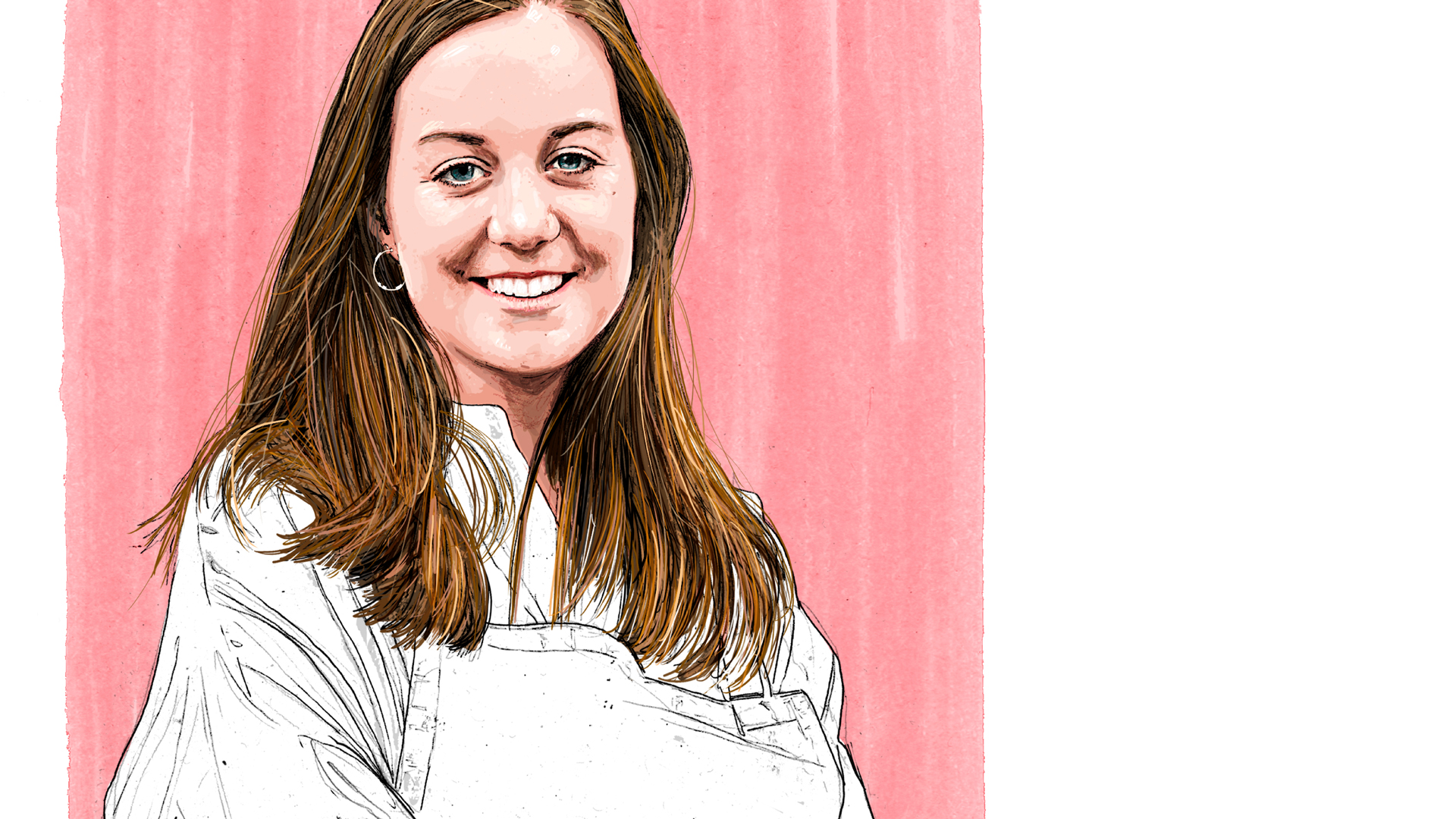

What people need to escape homelessness is usually tangible: money. But buffeted between hostel and job centre, saving cash is near impossible. That’s why Meg Doherty launched Fat Macy’s, a London catering social enterprise with a difference. As well as giving homeless people the experience they need to get back on their feet in the job market, it centres on a housing deposit grant scheme that removes the biggest barrier for people locked out of getting a home of their own.

After getting a degree in French and English literature in Edinburgh, Doherty took on social innovation and entrepreneurship course Year Here. At the same time, she started working in a North London hostel and was immediately surprised by the reality of homelessness for so many.

“The main thing I heard about time and time again was how hard it is for people to move out of hostels and temporary accommodation,” Doherty, 29, tells The Big Issue. “I didn’t understand why we created a system that gets people off the streets but then traps them in hostels and B&Bs for years because they can’t afford to put money down for a flat.

“A colleague of mine used to manage Jamaican-Caribbean cooking classes. There was such interest and love for this in the hostel. That’s what got me thinking – could we use food to help people save their deposits? That’s the hard thing – saving any money.”

The social enterprise Doherty dreamed up became Fat Macy’s in early 2016. (Now the founder works on it part time while balancing it with her other day job as an assistant programme manager with innovation charity Nesta.) It runs training programmes with people living in hostels, giving them kitchen and front-of-house experience at supper club pop-up events across the city as well as personal development and goal-setting work with mentors. The profits from each event go into a housing deposit grant scheme fund that trainees can apply for at the end of the programme once they find a suitable flat and have an employment contract, to prove they can afford to stay there after Fat Macy’s pay their deposit straight to the landlord.

“Setting it up was tough,” Doherty says. “Social enterprises got a bit cool in the years that I’ve done this so there is loads of great support now, luckily, but that wasn’t always the case. To start we did one supper club which was the minimum viable product – a set menu that the guys in the hostel had designed with me. We found a cafe, invited friends and family. At that point the idea was just to try to cook for that many people and make a little bit of money at the end of it. We probably made about 50 quid. But it took off from there!”