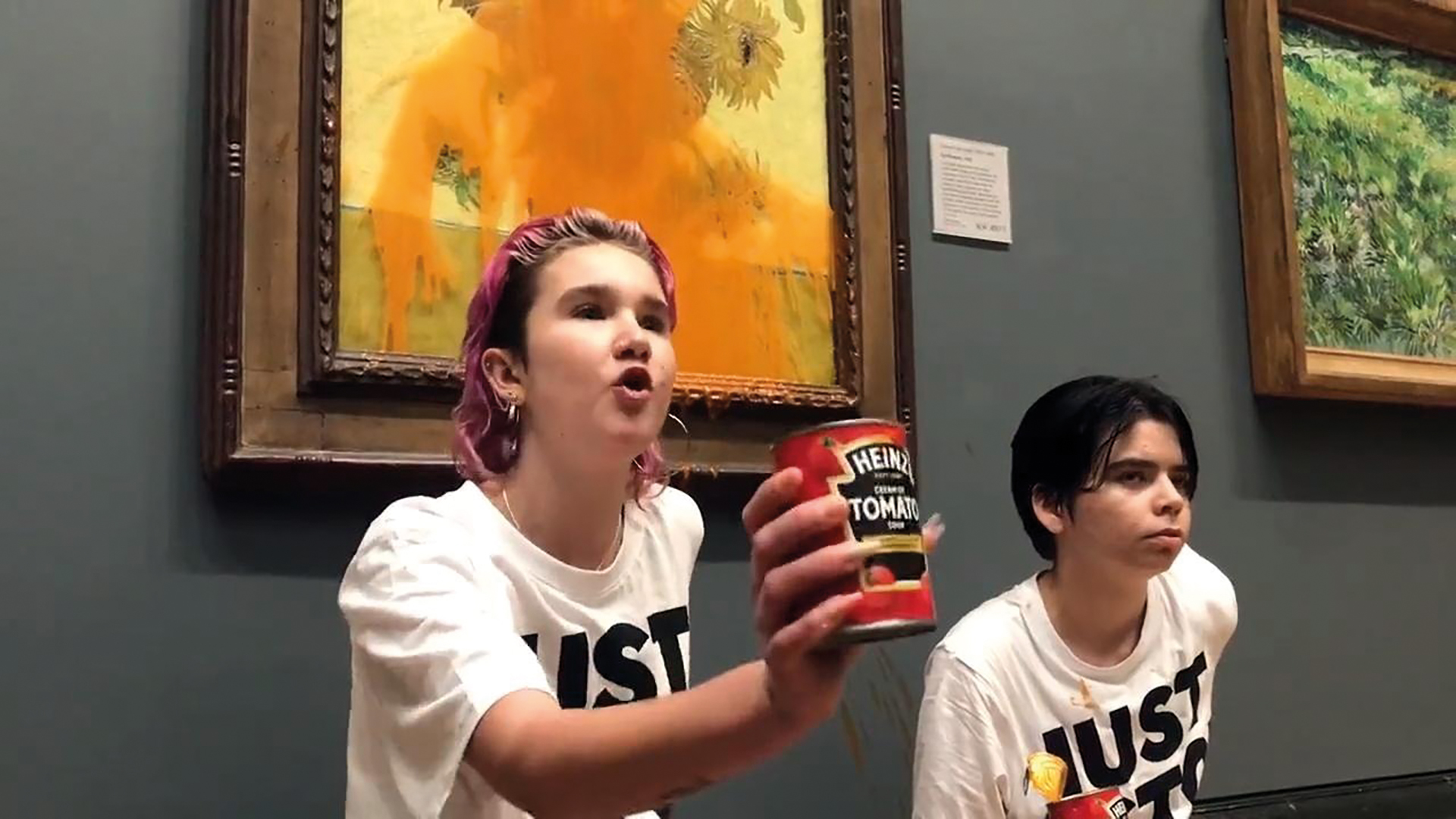

The sight of bright orange Heinz Tomato soup splattered over Van Gogh’s Sunflowers was too much to bear for some. Yes, of course, we support protests for the future survival of humanity, but this is a step too far. Perhaps this was the reaction Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland imagined when they entered the National Gallery in October, armed with one of Mr Heinz’s 57 varieties and some glue. The painting itself, hidden behind a glass screen, wasn’t damaged. Small matter.

“This is infantile vandalism and these people should be sent to prison… for life,” said a commentator on TalkTV, and so on and so forth. At the time of writing Plummer and Holland are set to face a jury in January – though not quite with a life sentence hanging over their heads. But their day in court is symbolic. It comes at the end of 2022, a year when the right to protest about the things you believe in has shifted and shrunk.

On one side, there are environmental protesters gluing themselves to roads, throwing soup over artworks, and tying themselves to goalposts during Premier League matches. They’re faced down by the government, defending the “law-abiding majority” against “criminal, disruptive, and self-defeating tactics from a supremely selfish minority”, as former Home Secretary Priti Patel put it.

The government’s main instrument in the battle was the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act. This new law, which gave the police powers to put noise restrictions on protests, was described as “the biggest widening of police powers to impose restrictions on public protest that we’ve seen in our lifetimes” by leading barrister Chris Daw. Resistance in the House of Lords meant some of the bill’s more draconian measures were stripped out, before it was passed into law in April.

It’s worth noting that some of these powers haven’t actually been used. In fact, The Big Issue discovered that the new powers on noise hadn’t been used at all within the first six months of the bill becoming law. But under old laws and new, protesters are finding themselves – not accidentally – in courtrooms. This year, as they’ve landed in court, climate protesters have adopted a new approach, using their defence as an extension of their protest – a chance to spread their message and appeal to the conscience of jurors.

One such group were seven women from Extinction Rebellion who had smashed windows at Barclays’ HQ in Canary Wharf, east London, in an attempt to “raise the alarm” over the bank’s investments in fossil fuels.