She added: “We are campaigning hard to encourage more social housing providers to provide furnished tenancies, and for the government to provide more funding for local authority crisis schemes and stop the planned cut to universal credit.”

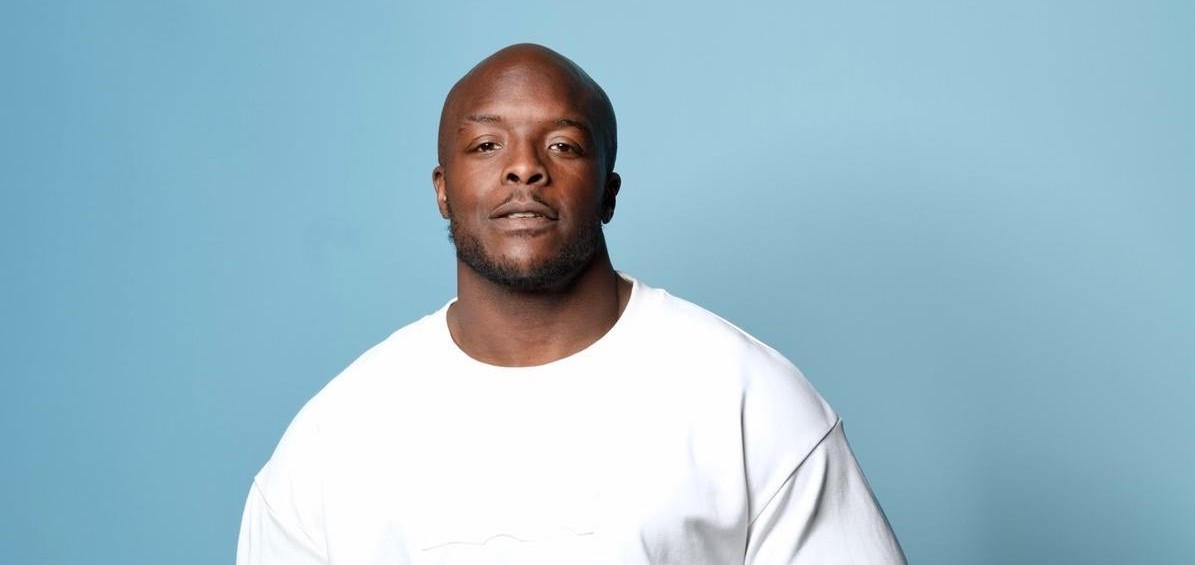

Akinfenwa joins a cohort of sporting role models, many of them footballers of colour, campaigning against poverty and injustice in British society — making headlines for their inspiring work off the pitch as much as their endeavours on it.

England forward Marcus Rashford, 23, last year forced Prime Minister Boris Johnson into a U-turn over free school meal vouchers amid fears of spiralling child holiday hunger. England winger Raheem Sterling last year launched an initiative to help disadvantaged young people. He was awarded an MBE by the Queen in June for his services to racial equality in sport, alongside midfielder Jordan Henderson for his charitable work raising money for the NHS.

“People always think that we’re footballers first, but we’re humans first,” Akinfenwa said. “What these players are doing, this new crop of individuals, they are showing that when something resonates with them they are not afraid to go out there and use their platform, their influence. And I think more people should.”

“Taking the knee is good in the sense that it consistently makes us aware, but it’s not the only thing that we’ve got to do,” Akinfenwa said.

Akinfenwa was raised on a council estate in Islington during the 1980s, in a Nigerian family with three siblings. “The things that we lacked materialistically we had abundantly when it came to love,” he said. He recalls playing football in the cage at every opportunity.

After stints playing at Torquay United, Swansea City, Northampton Town and AFC Wimbledon, he’s been at Wycombe since 2016 — becoming the club’s record poacher in its EFL era with 55 goals.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

When Akinfenwa spoke on Sky Sports this summer after signing his one-year deal, his voice was hoarse — he’d spent the night before cheering England’s 2-1 victory against Denmark in the Euro 2020 semi-final at Boxpark Croydon.

For Akinfenwa, it was powerful to see such a diverse, inspiring team achieve the most since 1966 while also taking the knee — sending a message to the world that English football is united in the fight against racial injustice.

“The England team showed what the UK is: it’s diverse, it’s many cultures, many blends, many characters,” he said. “It’s a beautiful thing.”

“I always say, taking the knee is good in the sense that it consistently makes us aware,” he added. “Of course, it’s not the only thing that we’ve got to do.” Racial injustice will not be solved overnight, he said. “But everytime we take the knee, it either reminds you, makes you aware or starts a conversation — and that’s what we need to do.”

Akinfenwa knows too well what it feels like to be the target of abuse. “It gets to you, we’re humans,” he said.

As well as the typical vitriol of social media, Akinfenwa filed a complaint to the FA last year alleging he was repeatedly called a “fat water buffalo” by Fleetwood Town staff. The FA cleared Fleetwood. Akinfenwa said at the time the FA missed an opportunity to stamp out racism, after writing on Twitter that the remark “dehumanises me as a black man.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

The racial abuse suffered by the three players of colour who missed Euro 2020 final penalties for England in July — Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka — sparked a backlash against government ministers.

“You don’t get to stoke the fire at the beginning of the tournament by labelling our anti-racism message as ‘Gesture Politics’ & then pretend to be disgusted when the very thing we’re campaigning against, happens,” England defender Tyrone Mings wrote on Twitter to Home Secretary Priti Patel, after she said in June fans have a right to boo taking the knee.

But for Akinfenwa, the response from the country was uplifting. A defaced Rashford mural in Manchester was quickly overloaded with flowers and well wishes.

“It’s a small minority that are ignorant and silly,” Akinfenwa said. When England rallied around its three young Black players, the negativity was shut down. “We are way more powerful as a collective.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Akinfenwa hopes his intervention on furniture poverty will have an impact on the hidden scourge of families that go without — and encourage action.

He is raising awareness for a campaign launched by Ryobi UK, a power tool company, and Central Aid, a Wycombe charity that helps poor families access second-hand furniture at low cost. Ryobi will provide tools and expertise for dozens of charities in the Reuse Network to restore knackered housewares for families unable to afford furniture.

“It is fantastic that footballers like Akinfenwa are donating their free time to support people who are struggling,” said Liam Evans, external affairs manager at Turn2us. “We urge Number 10 to show moral leadership on this issue and put forward practical issues to solve the symptoms and causes of financial hardship.”

In the pipeline is Akinfenwa’s mentoring charity, BMO State of Mind, which aims to coach young people to focus on their mental as well as physical fitness. “My mind is the strongest thing I own,” he said.

As the new season kicks off, Akinfenwa has been busy on the training ground working on his fitness. The older a footballer gets, he said, “the mind gets quicker but the body gets slower.” Wycombe are gunning for promotion to the Championship for the second time in three seasons after dropping back into League One this year.

Alongside charity work, rumours of Akinfenwa’s next chapter include punditry, a documentary, and even WWE wrestling. But he’s still getting used to the idea that, from next year, he’ll no longer be in the runnings for FIFA’s strongest player.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“Everything’s got an expiry date,” he said. With one year left on the game, he’s awaiting FIFA 22 rankings to see if he’s kept the crown. “I haven’t got any doubt on me being the strongest,” he said. “I see a couple people putting in the work, but there can only be one Beast Mode.”