“I’m going to advance a theory to you now,” begins Professor Brian Cox. “I’ve started to think that education is a national security issue. What you rely on in an open democracy is the ability of people to take an informed position but we’re not teaching people how to think and we are becoming unstable as democratic societies.”

How did we get here? 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, 4.6 billion years after the Earth was formed and 200,000 years since humans started plodding around the planet, we threaten to end it all every time a big vote comes around. Brexit, Trump… even the dance-off on Strictly cannot pass without the world seeming to tilt on its axis – in 2016 we were told: “People in this country have had enough of experts.” Oxford Dictionaries even crowned ‘post-truth’ as its word of the year.

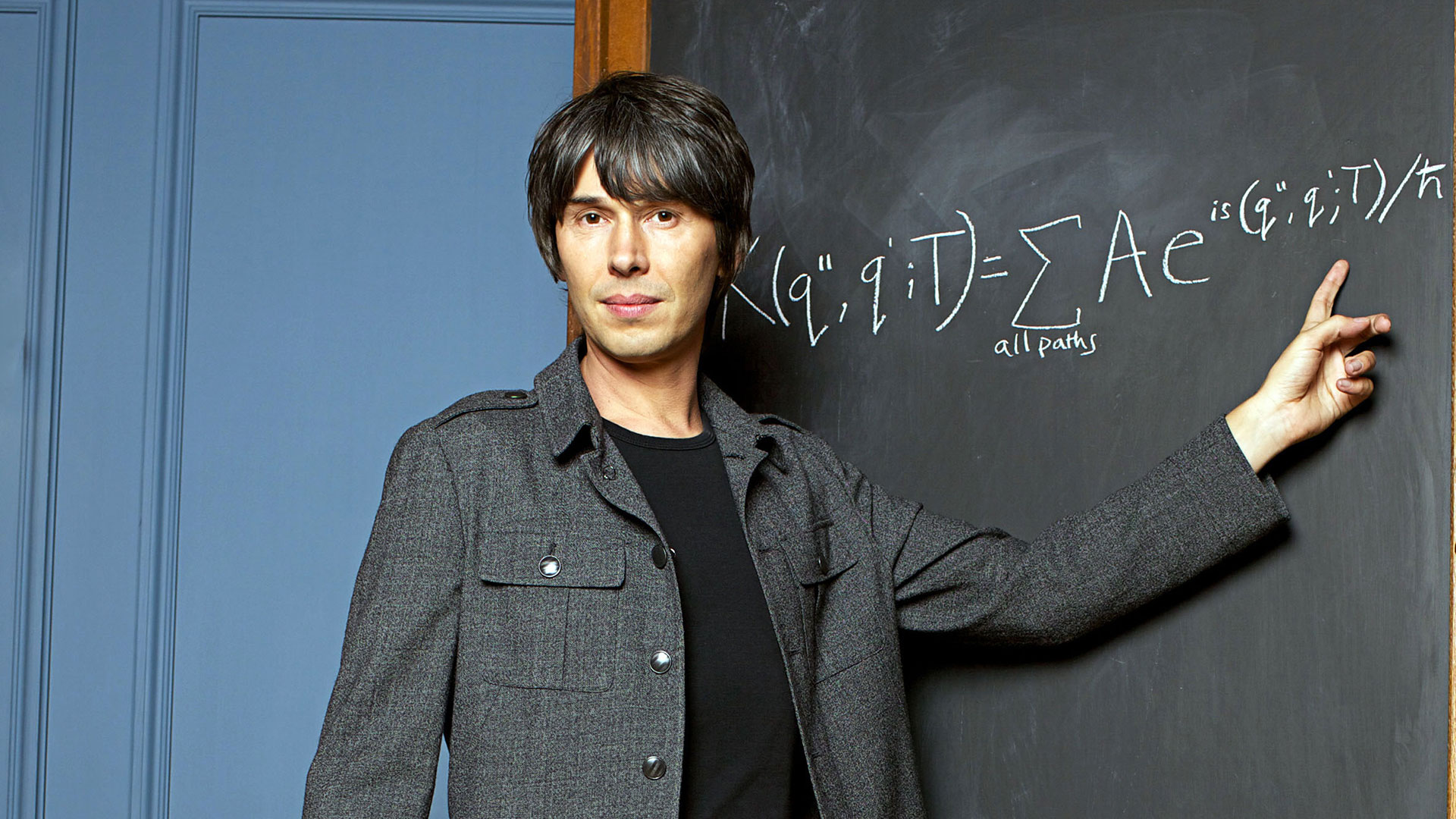

Brian Cox is a bona-fide expert. His day job is Professor of Particle Physics at the University of Manchester but in his spare time he is an author, TV presenter and Professor for Public Engagement in Science at the Royal Society (not to mention his work at Cern and for 1990s pop outfit D:Ream). Hailed as the heir to Sir David Attenborough – by Sir David Attenborough – the eternally awed telegenic star is pushing the frontier of human understanding and has reignited interest in science. He is in the midst of a tour, selling out theatres and arenas with his inter-stellar slideshow, accompanied by Big Issue columnist Robin Ince.

There is a misunderstanding of what science can be as a human pursuit

Before his evening show in Cheltenham, Cox, along with Professor Jeff Forshaw, co-author of Universal: A Guide to the Cosmos, is keen to talk about the value of reasoning and evidence. The American election is looming, a race that relegated facts and analysis and replaced it with bluster and hyperbole. But at this point it is still impossible to imagine a logic-defying victory for Donald Trump.

Yet it is imagination that Cox argues is key to our understanding of the universe. “You can’t take a picture of the universe as it was a billionth of a second after the Big Bang but using theoretical models and observations of the universe as it is today, you can infer what it might be like,” Cox says. “It’s an act of imagination to say I’m interested that leaves are green. Why are they green? The science is then in the way you go and investigate your question.

“There is a misunderstanding of what science can be as a human pursuit. If you want to design the wing of an aeroplane then you need to know how air flows and there are facts involved but the more fundamental aspect of science is that it’s a desire to understand nature. The fact that has turned out to be useful – extremely useful, it’s the foundation of civilisation – is a bit of an aside. It’s not surprising because obviously we live in the natural world so understanding it is going to be useful but that in itself is difficult to explain to politicians sometimes.”