There are no detention camps in Xinjiang, Chinese authorities said once the evidence and outcry became too much to deny completely – only vocational education and training centres. And those held there, they said, are not detainees at all but trainees who benefit greatly from their stay.

“The centres provide free education,” Chinese official Aierken Tuniyazi told a session of the UN Human Rights Council in June 2019. “The dormitories are fully equipped with radio, TV, telephone, air conditioning, bathroom and shower. A sports ground and library have been built.” The trainees’ personal dignity and freedoms are protected and they are allowed to go home on a regular basis, he said. Many had already “graduated” from the centres to live “a happy life with better quality”.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

This was the narrative carefully propagated by Chinese government and state media, and armies of online commentators. None of it corresponded with the experiences of Uyghurs, Kazakhs and others caught up in the crackdown on Xinjiang’s Muslim minorities that a 2022 United Nations report found could constitute crimes against humanity, and the United States and other countries have described as genocide.

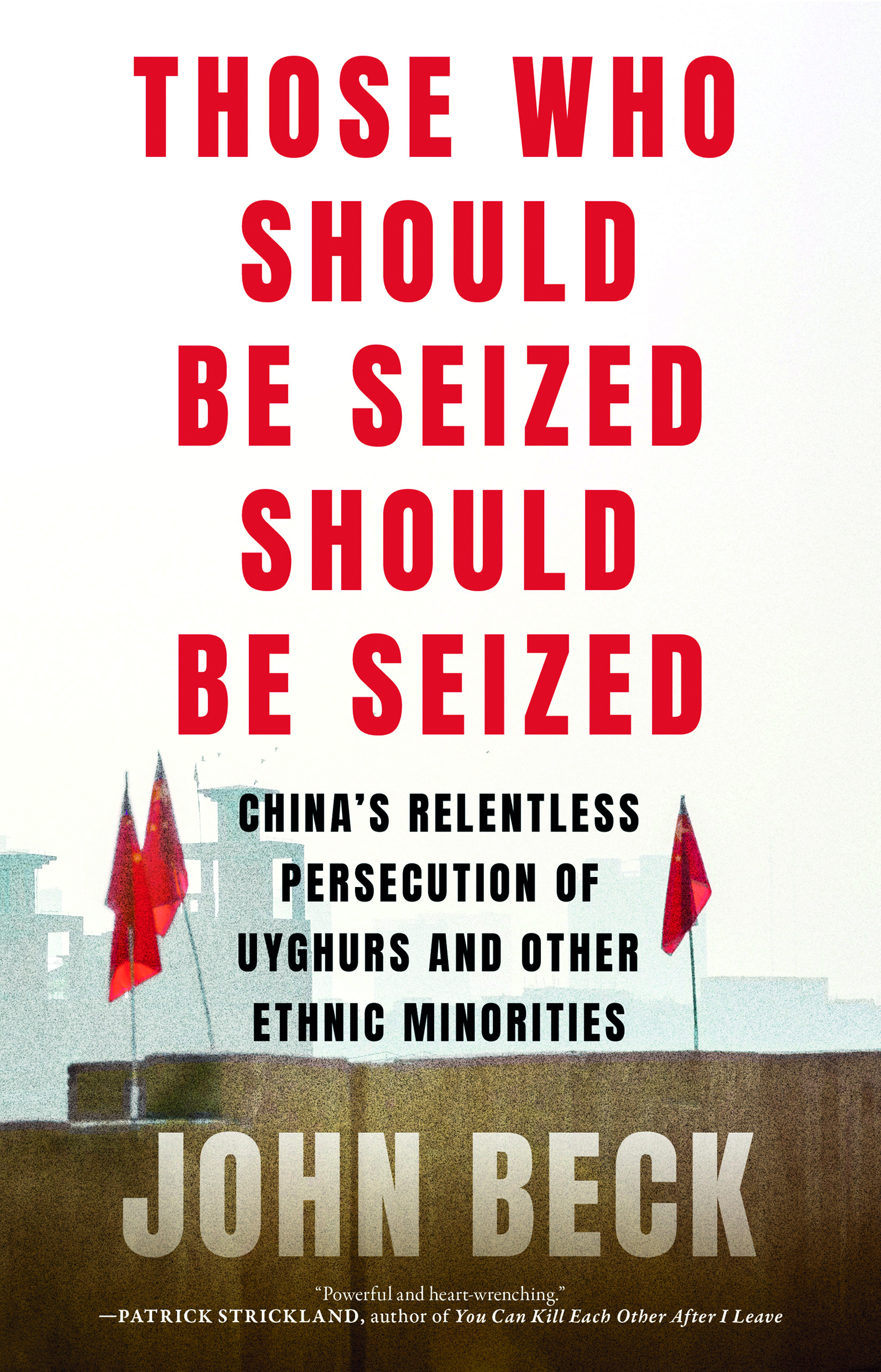

Only a tiny fraction of the estimated one million detained in camps and prisons managed to escape abroad. I spoke with a series of them in Turkey, Kazakhstan and the US while researching my book, Those Who Should Be Seized Should Be Seized, which investigates China’s oppression of its Muslim citizens. They had been held in different facilities across Xinjiang. All described systematic indoctrination, mistreatment and torture. Similar testimony has been gathered by rights groups and journalists and is supported by numerous leaked government documents.

People were taken to the camps for exhibiting what the Chinese government deemed signs of extremism – and that could be almost anything. Praying at the local mosque, wearing a headscarf or growing a beard. Quitting smoking, travelling to see family members abroad or just receiving a phone call from a foreign number. Saying “God bless you”.