At their high-water mark in the 1930s, when a movement towards swimming as an egalitarian leisure and health pursuit first splashed its way across the Channel from the continent, Britain had 169 lidos in all. Every spring and summer from Penzance in the south to Stonehaven in the north, open-air pools – named lidos after a beach resort in Venice – were mobbed by hundreds of thousands of prudishly bathing-suited and capped souls looking to enjoy not just an al fresco dip but also a place to socialise, relax and soak up sun and fresh air.

Then for many lidos the plug was pulled. The Second World War brought not only privations and austerity but also the requisitioning of many public leisure facilities, particularly along the coast, for military and civil defence purposes. Some never reopened. A lot of those that did struggled to stay afloat come the 1960s and the arrival of affordable foreign holidays. By the early 1990s Britain had scarcely 100 working historic outdoor pools left. The crumbling remains of rain-water filled lost lidos became emblematic of the faded glamour of many a seaside town.

That’s changed since the turn of the century, however, amid a movement towards restoring and reopening many of Britain’s run-down, abandoned and forgotten open-air pools. Be it because of growing appreciation of the health benefits of an outdoor dip, the popularity of “staycation” home holidaying and switching off for a while from hyper-connected everyday life, the iffy state of British beaches or just the keen actions of local grassroots community campaigners, lido levels are on the rise again – and all are welcome to dive in.

Plymouth’s Tinside Pool led the way in 2005 when it reopened for the first time in 13 years after a £3.4m refit, the result of a vociferous local campaign which had secured Grade II-listed building status for the iconic, half-moon Art Deco structure. Further inland, Hackney’s London Fields Lido has enjoyed enormous success since reopening in 2006, attracting around a quarter of a million swimmers annually. In a similar spirit to Bristol’s Clifton Victoria Baths, which reopened as an upscale multi-use facility called The Lido in 2008, the Edwardian King’s Meadow swimming pool in Reading last year was reinvented as the plush Thames Lido at a cost of £3.5m.

And campaigns have been launched to bring back the likes of Broomhill Pool in Ipswich and Cleveland Pools in Bath – the latter of which dates from 1815 and is believed to be the oldest surviving public outdoor swimming pool in the country. Hardy favourites such as London’s Brockwell Lido and Tooting Bec Lido, Hathersage Swimming Pool in Derbyshire and the Jubilee Pool in Penzance and Stonehaven open-air pool near Aberdeen have all enjoyed huge attendances in this summer’s heatwave.

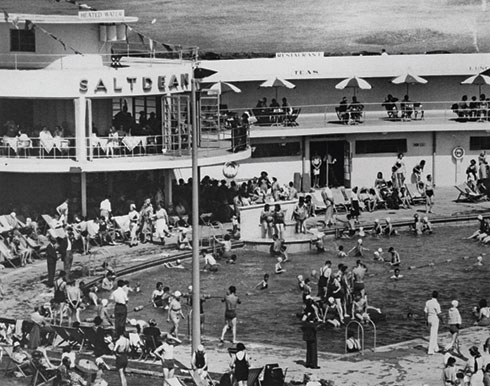

Sweltering days on the south coast have likewise ensured a record turnout in just the second summer since reopening for Brighton’s famous Saltdean Lido – an elegant Art Deco masterpiece designed by modernist architect RWH Jones which, apt to its location gazing out towards the English Channel, has the appearance of an ocean liner run aground. Albeit, as one of the volunteer directors of the campaign to save Saltdean Lido Sally Horrox cautions, don’t go assuming that bringing a beautiful historic pool back from the depths of dereliction has been a mere paddle in the shallow end. “I think we thought it was going to be a £5m project,” she says, “and it ended up being closer to £11m.”