One of the real questions when you write a book is why bother? What’s the point? When you write a book about trauma, in particular, there’s a longing to offer structures that help offer some kind of frame for understanding its disorientating impact. For me, that longing wasn’t an empty one; I know how much I have held on to the brilliant and thoughtful words of others, but it is difficult to communicate experience that is often outside language.

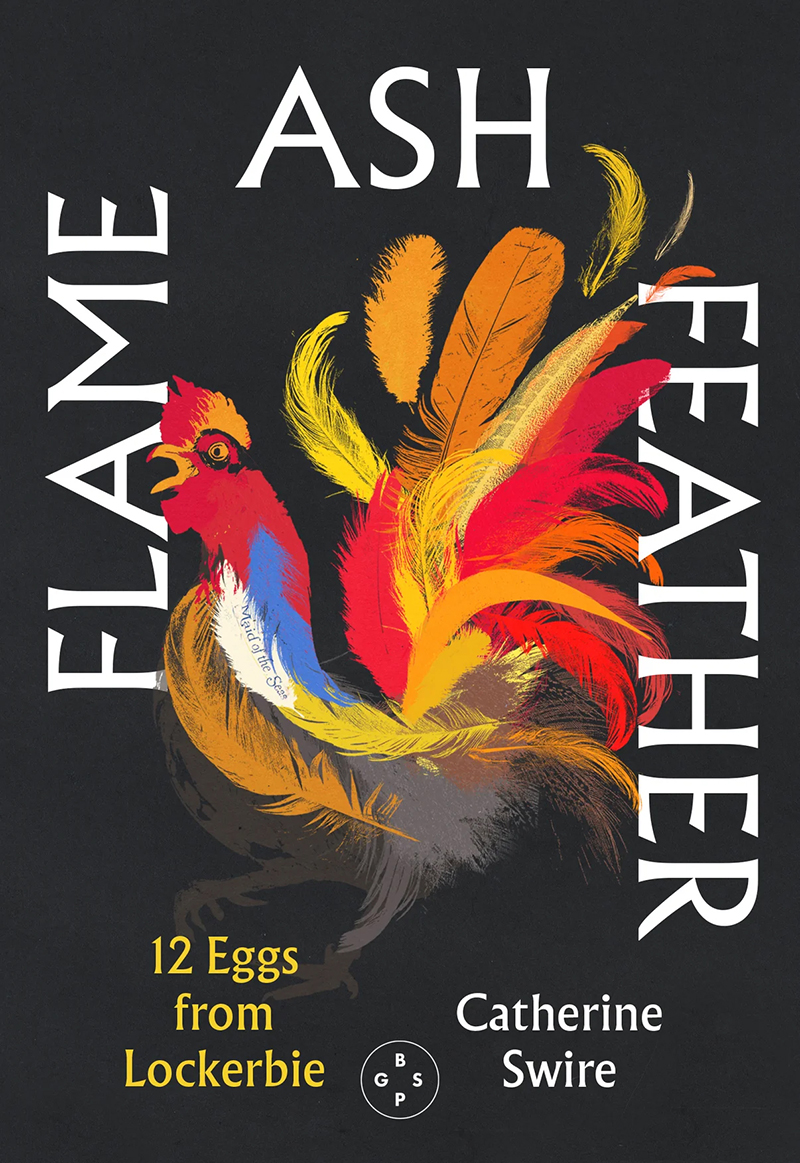

To write my very short and, hopefully, light book about living with chickens after a terrorist event, I drew on some of the most beautiful and harrowing accounts of loss that I have become familiar with. In particular, I used the medieval poetry that proliferated in the area where I live now – the Malvern Hills. The West Midlands can claim some of the most shockingly beautiful ancient poetry about nature and devastation in the English language. That poetry came out of intense national suffering; Britain lost a third of its population to the Black Death and whole communities and townships had to fold.

At the time of writing my book, I was facing some extreme losses, both real and imaginary, following on from the sudden, violent death of my sister in a terrorist attack. The illness and sudden departure of family and friends brought me back, as often in trauma, to a consideration of some of the impacts of that event. I began to connect those impacts with works from the ancient past.

One of my starting points was a poem written in part about the Malvern Hills called Piers Plowman, which shows at its climax the Harrowing of Hell, a brilliant battle of cunning, or ‘flyting’, a competitive slam for the souls of the dead. The poet who dreamed that journey to hell feels dislocated and is shown wandering from place to place without clothes and shoes, sleeping by streams. As he wanders, sleeps and dreams he catches occasional glimpses in the landscape of a natural harmony that escapes him, epitomised in the kinship of the fowls with “speckle-coloured birds”.

I spent a good deal of time looking after chickens over the last 15 years, as well as raising my two children in the context of divorce and debt. I was, I suppose, struggling to find words to explain how deeply and how intimately the chickens’ ordinary lives – and deaths – pecking in our garden, moved me. It was only through writing this short book that I realised how deeply my relationship with chickens was also an act of mourning for somebody very dear I had lost.

- Top 5 books about trauma recovery, chosen by Lech Blaine

- Poet and author Blake Morrison on grief and why he wrote so much about his family

One of the loveliest medieval poems of all time is Pearl, which tells the story of a dreamer who falls asleep and talks with his daughter, suddenly dead, who he imagines, partly, as a pearl – shimmering, white, refracting against his own despairing sense of separated decay and loss. I think now that poem was working in me too when I wrote the book, which evokes the shape of a smooth, whole egg “the colour and the feel of cool plaster” to hold each chapter.