I know where I was on September 19, 1965. I was 19, it was a Sunday and I was newly married and living with my wife in Edinburgh. On that day I went with her to the Botanic Gardens on the edge of the city, to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Now a colossal construction with hundreds of works and a vast building, it was then a small building among trees and grasses. I know I went there that day because I got the catalogue for an art exhibition of the works of Giorgio Morandi. I had never heard of him. How the hell have I moved all over the place, perhaps 100 times, and still kept the slim little catalogue?

I was astonished at Morandi’s work. It was so simple and undemonstrative. It was largely still lifes, though it did include a few simple and rather dull-looking landscapes. But there was something about the show and what Morandi did with so little.

His colours were mild greys, greens, pinks and cream. His subjects were jars and little pots – nothing to write home about. But with this he struck me as one of the best artists of the 20th century.

How can I say, hand on heart, Giorgio Morandi is as great as that, when he would bore so many people? By the time I was 19 I had trained my eye to look at paintings for over three years. I had put the work in. Putting the work in improves not just the eye for art but the mind for reading and thinking. I used art to lift myself out of a life of drifting and wrongdoing. Of being an anti-thinker, of not wanting to put myself out for anything other than the pursuit of girls and drink.

Morandi arrived suddenly in my life and turned my art world upside down. And also got me trying to think about what was going on. For I was surprised at my response. Why was I drawn to such simple and apparently dull artwork? I could not explain it. All I could say was that the thousands of hours I had devoted to drawing and painting, and looking at art and reading about it, had put me in the way of understanding Morandi.

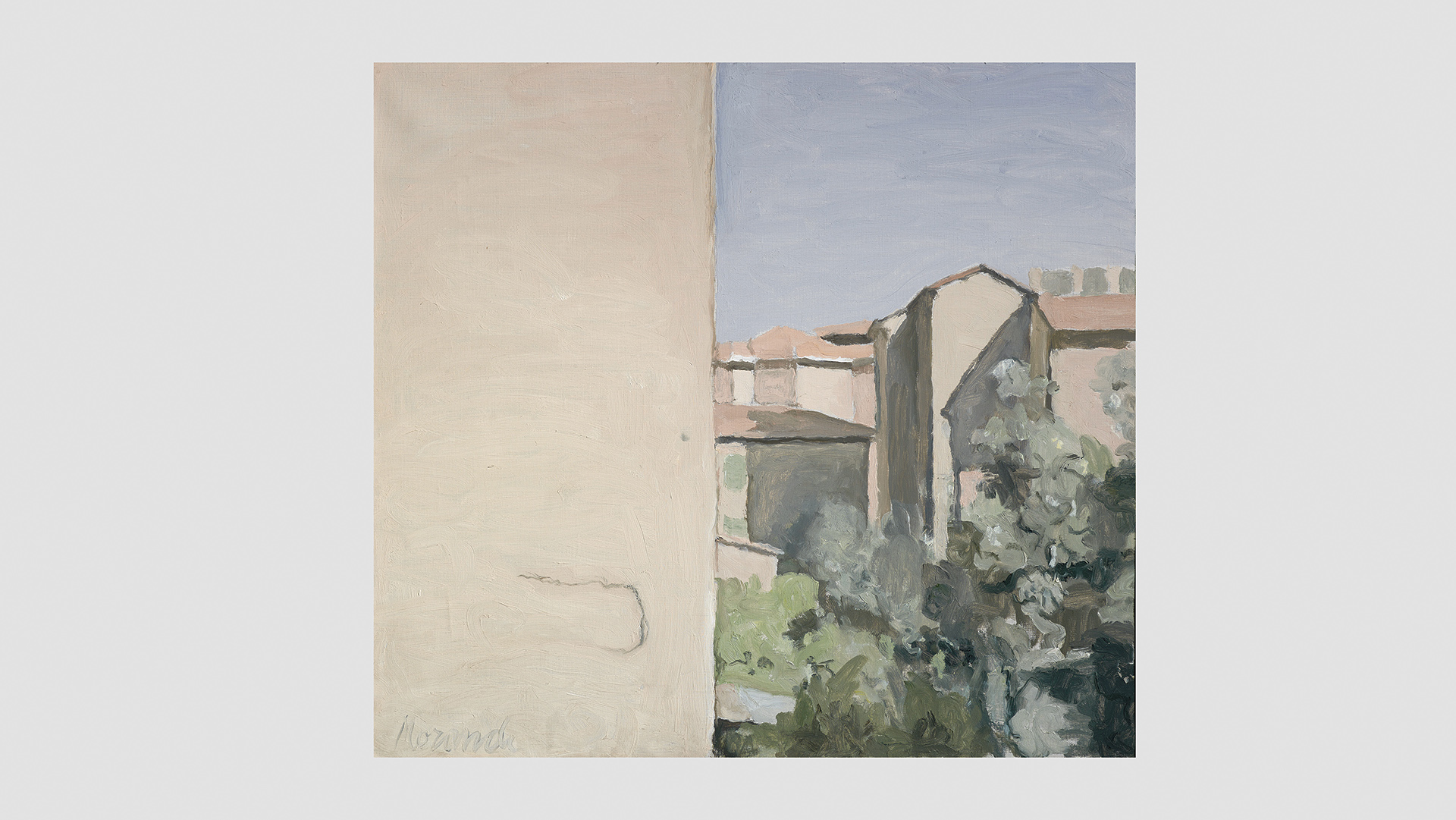

And Giorgio Morandi was a great challenge because his work has this bland appearance to it. For instance, Courtyard on Via Fondazza (1954) shows a house with trees, with almost half the painting a blank wall. What’s going on here? Was I just turning into a ‘pseud’ – the worst thing you could be called then? My mate Brian and his brother Mick the Mouth, who I grew up with, were convinced that when I talked about art I was just showing off.