Weirdly, I found myself agreeing when hearing retired Major General Tim Cross on BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme, saying that army recruitment is “not about being nice”, it’s about “fighting power” against the “Queen’s enemies”. This nakedly militarist agenda at least has the merit of honesty. The General has been irked by the fresh crop of British Army ads.

Marketing the military is a difficult business, with recruitment rates stalling. But the marketers seem to have settled on ‘belonging’ as the army’s selling point. I’d like to call out the lie.

There’s been a switch in the emphasis of the belonging message. Last year, you’ll have seen ads depicting live-action scenes of army life. The ad I saw most shows a lad sitting in the rain looking pretty haunted until he’s brought a cup of tea and gets his hair tousled by his comrades. There’s also the trooper teased as he tries to climb aboard a moving jeep. All cracking, relatable stuff – especially for me as they all appeared to be white men. The point was: you’ll face hardship but you’ll find a home in the army.

The imagery has switched to colourful animations featuring the words of serving soldiers. Each video answers questions like ‘Can I be gay in the army?’, ‘Do I have to be a superhero?’, ‘Will I be listened to?’ (that one’s a woman) and ‘Will I be able to practise my faith?’ (Muslim). The Army is being positioned as not just inclusive, but at the leading edge of social progress.

The previous campaign explicitly targeted 16-to-24-year-olds from the poorest three socioeconomic backgrounds. These new ads have a different emphasis. You can see why the advertisers identified a thirst for belonging among young adults. Economic recruitment – targeting the poor – is centuries old. Now they’ve set their sights on people who may experience other forms of marginalisation.

Exposure to war increases the likelihood of violent behaviour towards the self and others.

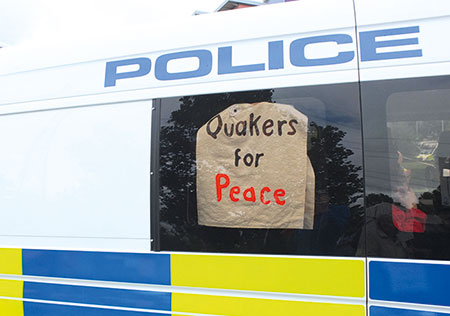

For Quakers, recruitment ads are part of the machinery of war, so of course we’d oppose them. But ‘this is belonging’ is a more basic untruth for a simple reason: no one belongs in war.