It was Rod Stewart who first mentioned the phrase ‘do as I say not as I do’ to me. We were chatting in a pub garden near his home in Essex. It was a lovely, sunny day, we’d had a kickabout in the car park, and he was having his photograph taken in a botanical garden of a Versace shirt for the front of The Times Saturday magazine.

We were both essentially being paid for being there, and to be honest I couldn’t see too much of what he’d done that wouldn’t have been worth doing. True there are a few moments in his recording career which even he admits are worth skipping over and a period of spandex leggings most would consider criminal but as far as wine, women, song and dance, Rod appears to have had a fairly idyllic life.

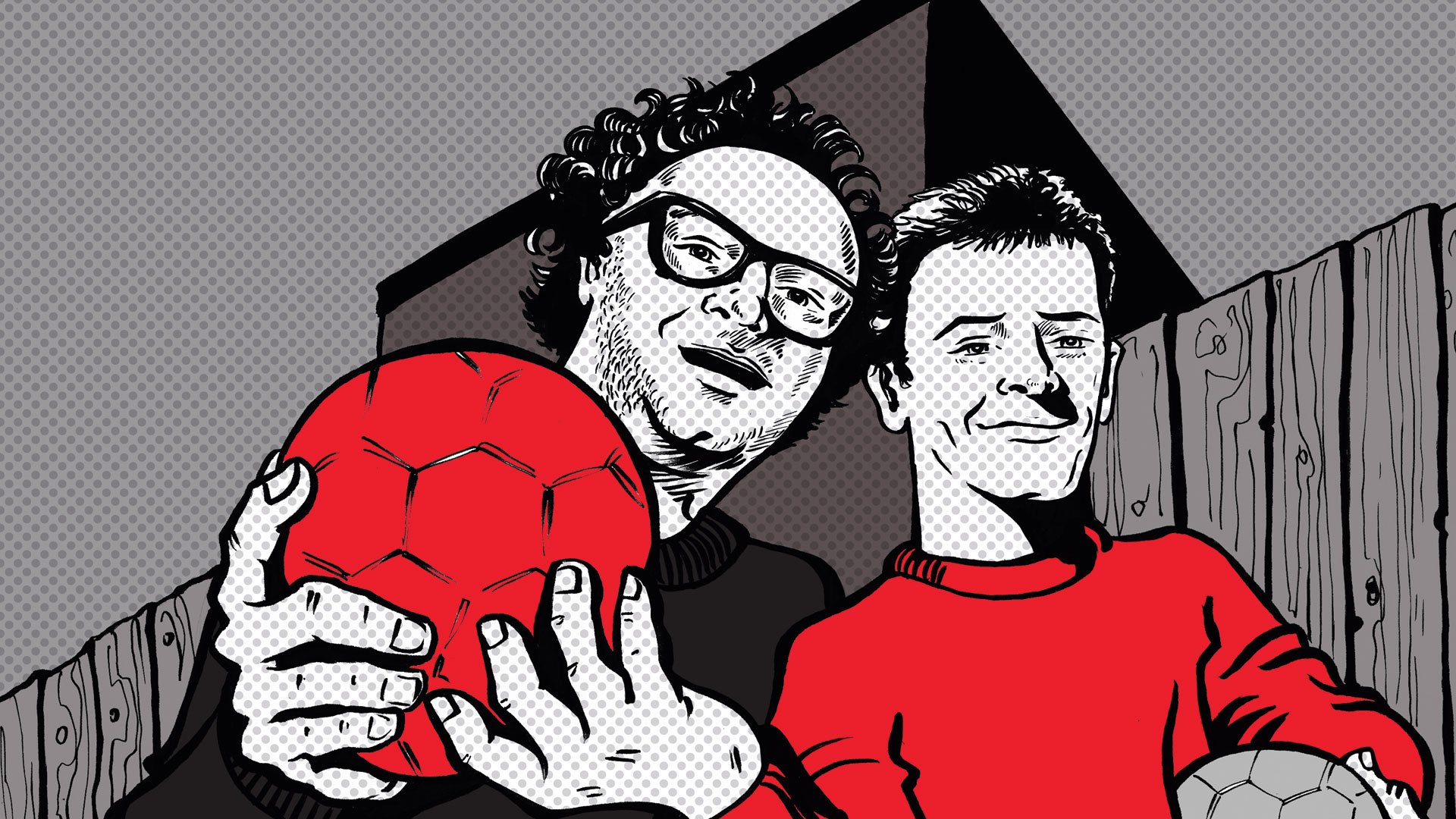

Only he wasn’t giving me the advice so much as explaining how he’d tried to pass on some fatherly advice about relationships to his eldest son Sean, who was just turning 18 at the time. Twenty years on I find myself in the same position. Parenting-wise that is, I haven’t moved to Hollywood and started an art-deco lamp collection. Last week my eldest son turned 16 and I find myself in a bizarre position of trying to guide him through the social and educational expectations of his mum, his girlfriend’s mum and himself.

I was living out a life entitled ‘50 Ways to Lose Your Liver’

Throughout his comprehensive school years I’ve had to sit at parents’ evenings and feel like a hypocrite as I’ve nodded along with his mum and his teachers trying to get him to apply himself because his best is really good but too often he prefers the easy route. In truth every one of the conversations we’ve had have been a replay of what my parents were told about me 30 years before at Lawnswood School, Leeds.

Which is what makes me worry most when I wonder whether his future years might replicate mine. Professionally it sounds great. I left school when I was 18, after some terrible mock A-level results. The offer to stay on and kick in was there from my inspirational head of sixth form, David Frost, but I knew I just wanted to go to gigs and write about them. Two years of unemployment and freelance writing later I was on the staff of the New Musical Express in Oxford Street, London. A minor miracle given it was the only job I wanted at a time when few employment opportunities of any kind were available.

So my job was music and journalism – worlds where excessive alcoholic intake was not only accepted but seen as a badge of honour. I’d sit and read books about Iggy Pop and the Stones, others by Hunter Thompson, Charles Bukowski and Jeffrey Bernard. Scanning the Lunchtime O’Booze column in Private Eye for tales of Fleet Street maniacs behaving riotously. And my behaviour responded accordingly, snorting so much speed before an anticipated confrontational interview with Zodiac Mindwarp I came back and puked vodka and orange all over the editor’s office.