In a world entrenched in race and class divisions, technology unites us all. You may have lost count, but on average we swipe our phones 2,617 times per day, checking for notifications, updates and messages every 12 minutes.

But the fact remains that the industry is far from diverse. Only four per cent of tech workers in the UK are people of colour. The tech sector not reflecting society has unexpected implications, some more serious than others. With everyone drawn into virtual meetings, for business or pleasure, during lockdown and beyond, inevitably participants are tempted to make things more interesting by changing their background. But the algorithm used to work out what the actual background is sometimes identifies darker skin tones as the area to replace, pasting the Golden Gate Bridge (or other exotic landscape of choice) over a user’s face.

More seriously, facial recognition technology increasingly used by large organisations or law enforcement is repeatedly shown to confuse black faces, and some infrared hand gel dispensers don’t recognise darker skin tones.

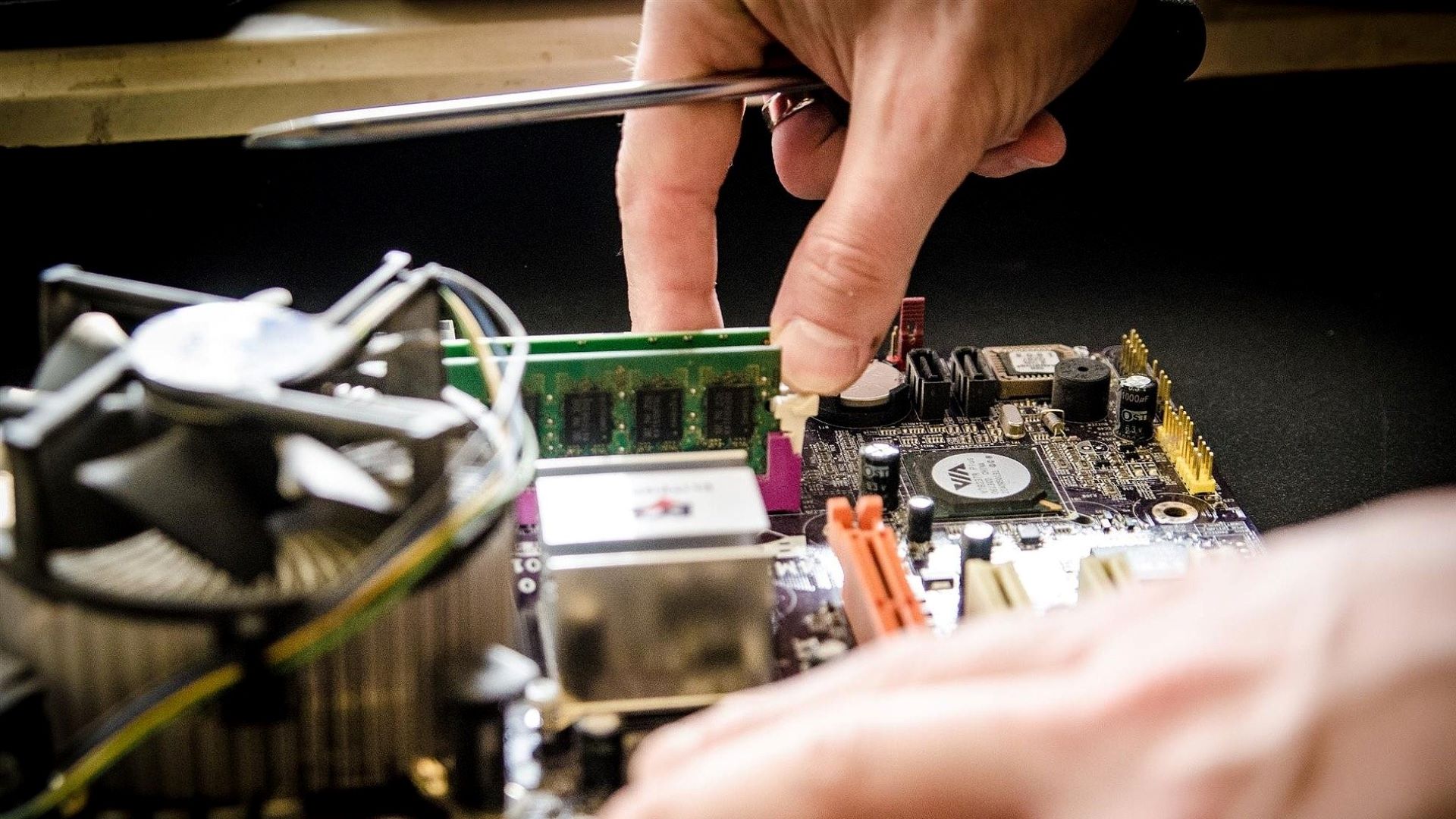

“This ‘diversity thing’, as some people describe it, boils down to being a life or death issue,” says Josh Babarinde, 27-year-old CEO of Cracked It, a social enterprise that trains young offenders, or those at risk of offending, to repair smartphones. “If someone of colour cannot wash their hands then that individual is going to be at a greater risk of contracting coronavirus and spreading it. Then it’s no wonder that the report by Public Health England recently found that black men are four times more likely to die from the virus than their white counterparts.

While Building Back Better is a catchphrase for post-pandemic thinking, Babarinde believes it is essential that diversifying the tech industry and hearing from under-represented voices is part of the process. And, he says, companies will be forced to do this for one reason or another.

“There were just so many arguments for why diversity and inclusion, whether on an ethnic, gender, disability, sexuality or socio-economic basis, is critical. It’s just not fair that some people get more opportunities than others, and those cycles just repeat themselves. If young people beginning their careers look at a sector like tech and think it doesn’t really look like them, they consider something else. What a waste.