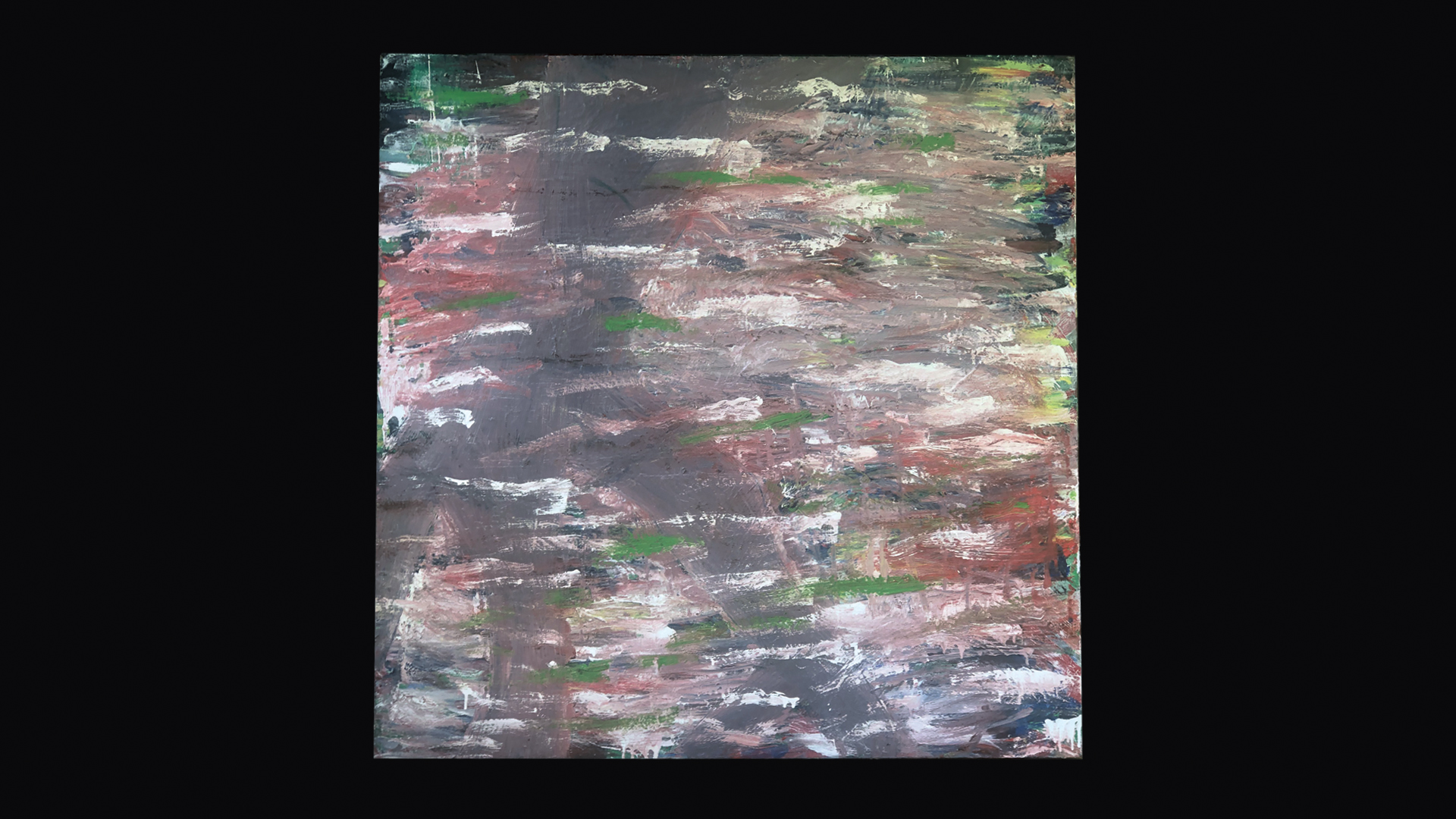

It’s very difficult to explain a large painting I worked on when deep in Covid. The painting is five-foot square, so it’s sizeable. Few walls could take it. It is supposedly a view of a tree reflected in a river. But who am I kidding? It’s really a load of colourful marks on a flat square. It went through a number of transformations the week I had Covid, but it did not get interrupted by the lingering pandemic. I just chugged on at it, adding stains and, at times, removing them.

The first problem of explaining the painting, which at the moment is untitled, is that it seems to me to have a value. It seems to have meaning, perhaps not as a river with a tree reflected in it. But what is it of, or about? If I go close up I can see the paint marks overlaying each other and I can, and do, enjoy the look of it. But it would possibly be unfathomable to the many, to most, if it ever gets shown. It just works for me. And having been looking at stains and splodges for perhaps 60 years, I can kind of make sense of it. Kind of. But I’m not so sure I’m not wasting my time.

I have other paintings that I have done and hang on walls that are of people, pots, trees, nudes. They seem to work, or not, according to the visible world that they are a part of. But these abstracts, or near abstracts, or riverbanks that end up as stains, are a different kettle of fish. This might just be painting for me and me alone.

In 1958 my father worked on building a kitchen for a multimillionaire on Park Lane in London’s West End. He got on with the wealthy man, who would occasionally appear to look at the progress. The kitchen was being transformed with a new material called ‘Formica’ – a shiny, hard, clean-looking material that could cover up anything that looked old and grubby.

One of the advantages of the job was that my father could take away all the offcuts. Hence we became, in our block of Fulham council flats, the first to have a Formica-topped breakfast bar. Gone was the rickety table and us sitting around it. In came the breakfast bar where we sat in a row. And the Formica design was incredible. Colourful, loud and mad. Perhaps 10 years before, Jackson Pollock (“Jack the Dripper”) had poured paint over canvas on a floor and stunned the global art world. Now we sat in our Fulham kitchen with a Formica’d kitchen that took Pollock-like drips and reproduced them en masse. We sat in a riotous array of colour and squiggle.

Art had jumped the fence of life and joined us in our kitchen. And increasingly people got used to stains and squiggles as a backdrop to drinking in a cafe or pub, or walking on the floors of shops. We all unconsciously became interior designers. The revolution in taste that my father helped launch in a Fulham kitchen soon engulfed the world. I explain the above because now I think people could look at my painting and not have to go through the history of art and the stains and splodges of the 20th century and say “I like it”, or not. We have been ‘visualised’.