I am a surgeon and I love my job, mainly because of what I can do with my hands. That’s where the name of my profession comes from: ‘surgeon’ in Greek literally means ‘handyman’. As a kid I loved my Lego; as a surgeon I love to stitch and cut, dissect and connect – blood vessels, intestines, muscles. I guess my colleagues from centuries ago must have felt the same joy in performing operations. Yet, I would never have wanted to become a surgeon if I had lived in the past. To be more precise, if I had lived before October 16, 1846 – the day anaesthesia was introduced in operations.

Why did these surgeons choose to take up such a cruel profession?

What did surgery look like before that date? There are many gruesome stories about famous and obscure surgeons wielding their knives on unfortunate patients. If they survived, it was usually not because of the operation, but in spite of it. More often they did not survive. My job would have been nothing less than a nightmare, not only for the unlucky patients, but definitely for me too. I’m not sure I would have had the guts to cut off someone’s leg without anaesthesia, and I most certainly would not have been able to bear the responsibility of so many patients dying. Surgeons of long ago had to be masters of speed: the shorter the operation, the shorter the pain. Napoleon’s army surgeon, Dominique Jean Larrey, was said to have amputated seven hundred legs in a row. The butchery lasted for four days – that’s probably less than a minute per leg.

In the 17th century, King Louis XIV of France developed an infection in his upper jaw from eating too many sweets. A rotten tooth had caused an abscess. Louis was in a bad way and there were fears for his life. Several surgeons were summoned. One of them stood behind the king to hold his head firmly against the back of a chair, with one hand on his forehead and the other forcing open his mouth. A second surgeon must have stood to one side to pull the top lip out of the way to ensure a good view of the upper jaw. A third would have been at the fireplace, warming up a branding iron. From his perilous and constrained position, the king must have been frightened to death when he saw the red-hot iron approaching him. The heat in his mouth, the stinking smoke and the excruciating pain must have felt like torture, but Louis bravely endured the ordeal and soon recovered. He was left, however, with a hole in his palate between his oral and nasal cavities. The result: soup and wine would pour out of his nose when he drank.

Why did these surgeons choose to take up such a cruel profession? Were they sadists, enjoying what they did, or heroes, who were willing to accept the potentially terrible consequences of their attempts to save lives? Either way, not many people wanted to become surgeons. Smart people would choose better jobs. As a consequence, trained professionals or academics were scarce in the surgical trade. Surgery of the past not only lacked medical resources, like anaesthesia, but intellectual ones, too.

In the 18th century, London surgeon John Ranby caused the prime minister, Robert Walpole, to bleed while trying to remove a stone from the honoured gentleman’s bladder. This was a dangerous but well-known complication from the operation. Ranby, however, could think of nothing better to solve the problem than bloodletting, an absurd treatment of course for someone that is already bleeding to death. Ranby was also surgeon to Queen Caroline, wife of King George II – she must have had her doubts, once reportedly calling him a “blockhead”. When Caroline fell ill, Ranby operated on her by candlelight, managing to set the doctor’s wig on fire and, more seriously, inflicted irreversible damage on the queen. She too died under his knife, and although Ranby was knighted for trying to save the monarch’s life, we now know that both the prime minister and the unfortunate queen would have lived if they had never encountered the famous surgeon.

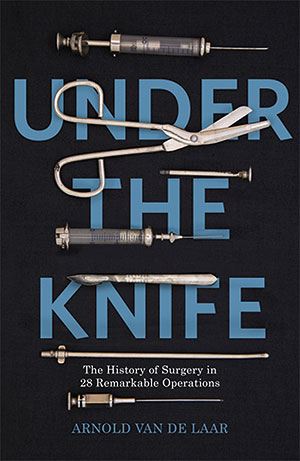

In my book Under The Knife I present 28 famous patients and operations in the history of my profession, from the dark ages of the past to the high-tech present. You can read about the bullet wounds of John F Kennedy, Pope John Paul II, Peter Stuyvesant and Lenin; the cancer on Bob Marley’s big toe; the punctured heart of Empress Sissi; the ruptured artery of Albert Einstein and many more.