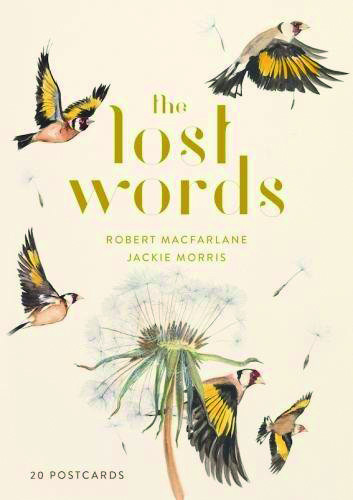

It started as spur of the moment decision. A woman called Jane Beaton was so taken by The Lost Words, Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris’ book about disappearing words from nature, that she wanted to get a copy into every primary school in Scotland.

Using crowdfunding, Beaton, clearly a determined woman, set about raising £18,000 to get the book to all 2,681 schools. They raised over £25,000 within 70 days. Beaton is now aiming to go beyond primary schools. It was a remarkable, noble plan, and an incredible achievement.

And Beaton has stirred something. There are similar initiatives in Wales and many English counties too. The book has grown.

Macfarlane, one of Britain’s greatest nature writers and a regular contributor to The Big Issue, has said he and illustrator Morris were “overwhelmed” by the response. That’s hardly surprising. Their book is in the vanguard of a noteworthy double change.

First, the aim of the book, to reintroduce nature words that were being lost from a generation of children as other words competed and pushed them aside, is connecting and working. And – more tellingly –they are showing the wonderful, visceral and sometimes life-changing power of books. When a book connects it opens up something that never closes.

World Book Day is this week. It’s a construct, of course, but it’s an important one. It aims to encourage potential readers wherever they are.