The costs are astronomical. The hype is obscene. They are also eloquent. But what do they say? Why do we care so much?

It’s not that pets are all good. They’re reservoirs for all sorts of diseases, cats kill more than 25 million of the garden birds you’re trying to attract, the dog will hump the leg of the fastidious guest you’re trying

to impress, and when he’s finished will exhale halitotically into her face and romp off to bite the postman. Yet when the dog dies you and the kids will be devastated. What’s going on?

Read more:

Whatever it is, it’s been going on for a while. The dates of wolf domestication are much debated, but let’s pick up the story in the Chauvet, in the Ardèche, France. In the floor of one of the famous caves there are two sets of footprints. A boy – perhaps eight or 10 years old – and a proto-dog were walking alongside one another 26,000 years ago. The cave was dark and frightening. Human life is a walk in the dark. It’s less scary if there’s a dog at our side.

Dogs grew up with us as we grew up as a species. They are part of us and we are part of them, and the solidarity with them, and so with our own origins, feels amazing. That’s not romantic hyperbole: it’s physiology. When dogs and their owners stare into one another’s eyes, levels of the bonding, feel-good hormone oxytocin rise 300% in humans and 13% in dogs (which might mean that you love your dog more than twice as much as he loves you).

When you stroke your dog or your cat, its natural opiates (endorphins) rise. They might rise, too, when you feel the animal’s fur against you. We might be giving one another a heroin-like high. Hospices make elaborate arrangements for pets to come to their owner’s bedside. It must reduce the doses of morphine. I’ve heard of one hospice that accommodated a horse.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Pets listen respectfully and sympathetically when humans don’t. Almost all pet owners talk to their pets, and many think their pets talk back. It’s good to talk. Talking is the mainstay of many psychological therapies.

Pets teach us a lot about life, and how to live well. Many of us learn about sex by watching dogs tied together behind a bush. Their stoicism, fidelity and their ability to forgive are splendid moral examples. Animals teach children how to care; how to be empathetic and how to deal with death. They don’t judge us. They are tutors in the core principle of dignity. They make us into liturgical creatures. The finest sequence in modern TV is from the BBC sitcomOutnumbered, where Karen buries a mouse in the garden, intoning solemnly over the grave:

Brethren, we are gathered here in the bosom of Jesus to say goodbye to this mouse, killed before its time. We have given it bread and cheese for its journey to heaven, or at least if it goes to hell, it will have cheese on toast… Dust to dust, for richer or for poorer, in sickness or in health, may the force be with you, because you’re worth it. Amen and out.

Karen was humanised by that mouse.

To have a wolf prowling round the kitchen (or its photo on our desk in the office) reminds us of what we really are. For almost all our history as behaviourally modern humans we’ve been hunter-gatherers: wanderers, with a clairvoyant relationship with the non-human world. We were a part of that world. We didn’t swagger colonially through it, regarding it as a resource. We can and must get back to that way of being. There are real reasons for hope. For if you strip the suit from a city trader you’ll find an Upper Palaeolithic bison hunter beneath. We’ll have better personal, societal and political lives if we live as the creatures we constitutionally are.

And the animals curled up at our side, or going round in the treadwheel, or nibbling grass in the

garden, can help. They rewild us, and therefore civilise us, and therefore make us thrive.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

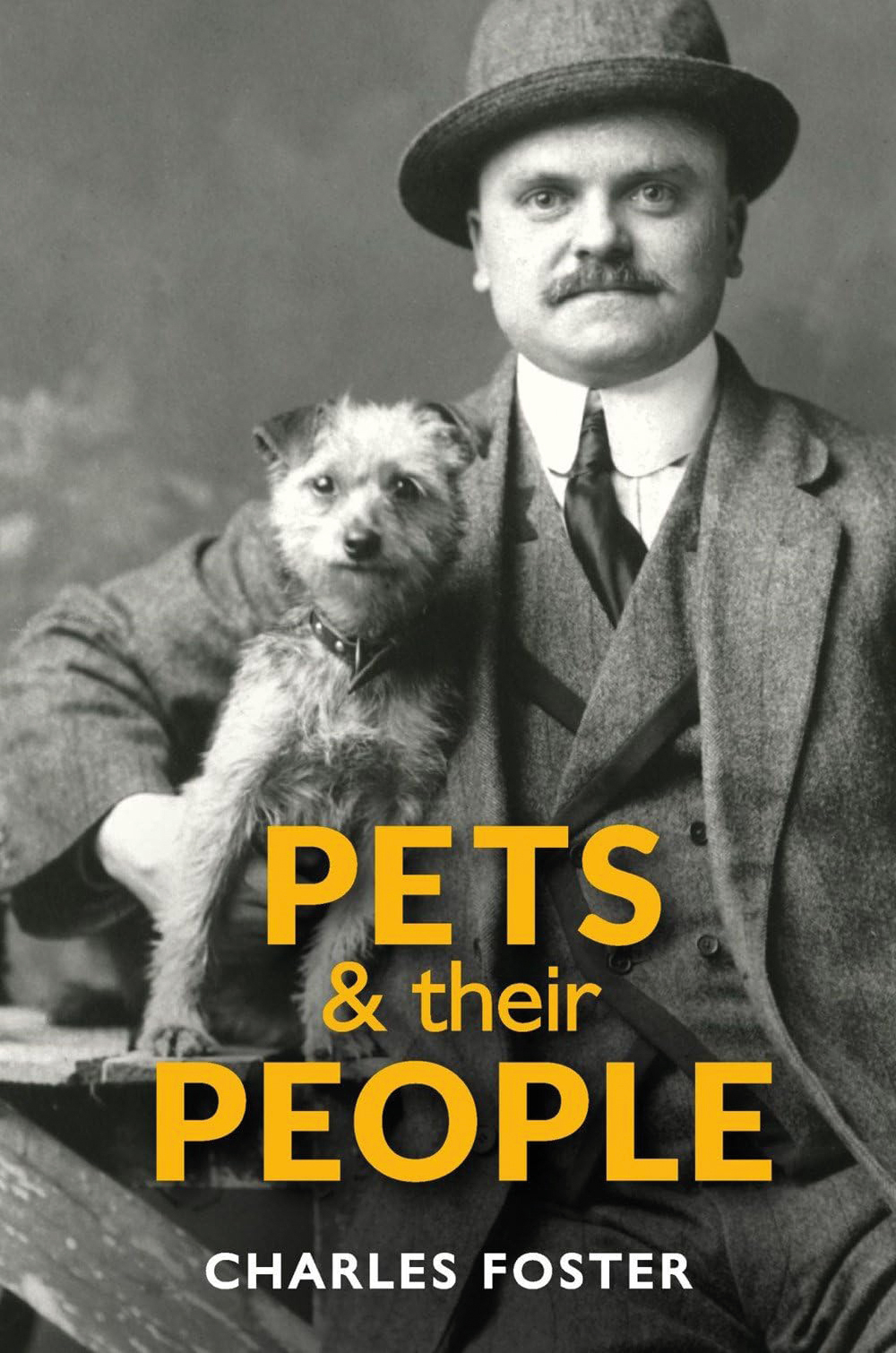

Charles Foster is the curator of an exhibition, Pets and their People, opening at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, in March 2026.

His book, Pets and Their People is out now (Bodleian, £25). You can buy it from the Big Issue shop on bookshop.org, which helps to support Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more.

Change a vendor’s life this Christmas.

Buy from your local Big Issue vendor every week – or support online with a vendor support kit or a subscription – and help people work their way out of poverty with dignity.