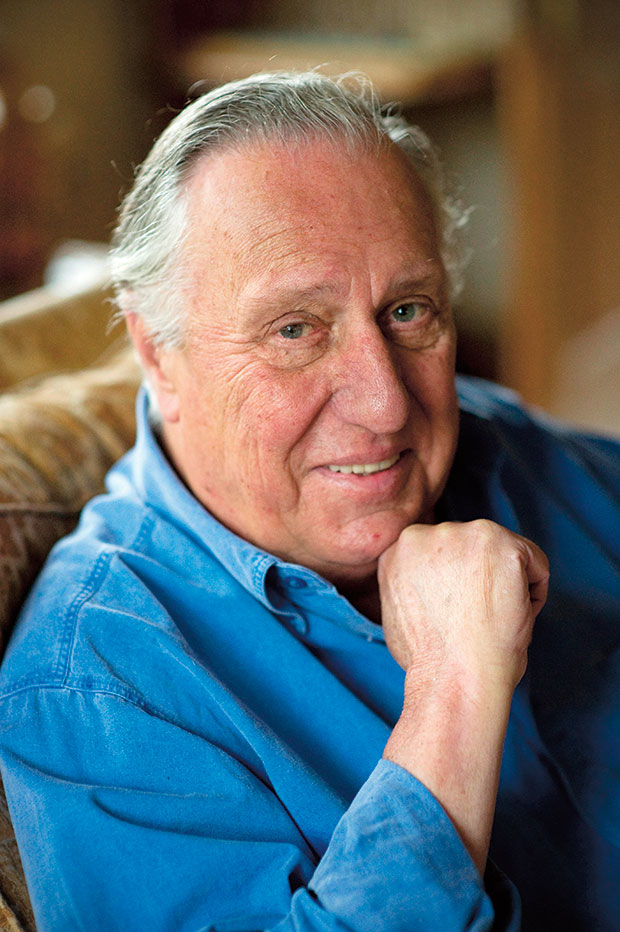

I was a very impatient 16-year-old. I was the scholarship kid in a very snobbish public school and I didn’t like it. I left as soon as my dad let me. I was in a hurry, I wanted to travel, I wanted to see the world. But most of all, I wanted to fly.

After school I was determined to join the RAF. I was raised during the Second World War and I had pictures of fighter pilots on my wall. My big dream was, one day I’m going to fly a Spitfire. These were the days of national service so I was a bit odd; all my contemporaries were trying to get out of it and I was trying to get in early. Everyone going one way and me pushing the other – that’s been a common factor of much of my life. I joined the Air Force when I was underage, and at 19 I got my wings after two years. I asked for a guarantee that I’d get a Hunter, a single-seat frontline jet fighter, if I stayed on. They couldn’t give me that so I decided to leave and fulfil my next ambition; to see the world.

I decided the best way to travel and make money was to become a foreign correspondent for a newspaper. I did three years in a daily provincial in Norfolk, then I got a lucky break. I got a job at Reuters news agency, then the guy stationed in Paris got a heart murmur and had to come home. A man stuck his head around the door of my office and said, anyone here speak French? Within days I was on the plane to Paris.

My life has been a series of being given chances and grabbing at every one of them. I’ve taken some big leaps, some of which could have been career killers. I was sent to cover the Nigeria civil war by the BBC, from the rebel side. I reported exactly what I saw in eastern Nigeria, which became Biafra, but it wasn’t what the Foreign Office wanted to hear. I was summoned and accused of biased reporting. They said, that’s not what we’re being told. I said, do we work for the Foreign Office? “Don’t be impertinent.” So I said, tell you what, screw you. I’m resigning.

I got my spirit from my dad. He was a shopkeeper in Ashford but he had seen a bit of the world, when he was a rubber planter in Malaya. He was tolerant and kind, very patriotic and loved this country. But his father was Irish and he had this rebellious streak of what they call being ‘agin the government’. If someone in authority ordered him to ‘come here’, he’d say ‘why?’ I think that’s why when the stream flows one way, I like to have my back to it. But that can destroy you, taking on the establishment. I was lucky, did all the wrong things, and I came out good.

After I resigned I went back to cover the civil war as a freelancer in Biafra, this awful story of these dying kids. It came to be a huge international story, which I was right in the heart of. The Nigerians came to crush the Biafran people, and they put a price on my head, so I had to get out. I was eking a living as a freelance journalist but I was in debt. So I had this crazy idea to write a novel. I knew the chances of it being a bestseller were thousands to one. But I went ahead and wrote The Day of the Jackal. And after that, everything changed.