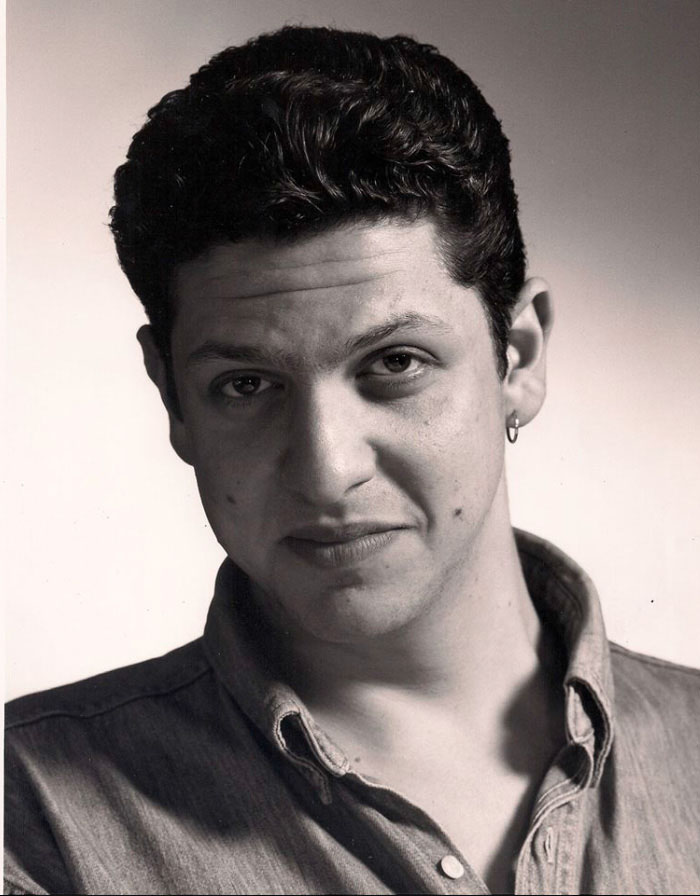

At the age of 16 I was the youngest child of an extremely successful and famous person [journalist and TV agony aunt Claire Rayner], and I was trying to find my own way in the world. My 16th was the most dramatic year of my adolescence, for a bunch of reasons. It was the year that I lost a lot of weight, and weight had been a preoccupation throughout my young life. It was the year I was thrown out of school for four months and plastered all over the national press. And it was the year that my closest friend was killed in a mountaineering accident. So it was a very, very dramatic year for me.

Losing my friend David when I was 16 was a terrible thing. We were very, very close friends. He went to a different school in Hampstead which was populated by the children of the liberal intelligentsia; they were all very hip. They went on a mountaineering trip to Snowdonia and I was woken on the Saturday morning by my mum knocking on the door saying there’s been an accident involving kids from David’s school. She went to call the emergency number, and they told her David had been killed, and she told me. I burst into tears. It was absolutely shocking. And then, the funeral. Many religions have a tradition of picking up a handful of earth and throwing it on the coffin. But the Jewish tradition is that the men pick up the shovel and they bury the coffin themselves. It’s proper work. I’d never done it before and I found myself being pushed to the front to do it. And it was shocking, helping to bury my friend. I still think regularly about him, and what he might be doing now.

One very positive thing did happen after David’s death. David was Jewish and there’s a thing called Shiva [a week-long mourning period following a death] when [family and close friends] gather for prayers. I went every night and I came to understand the importance of it. And a bunch of his friends from school came to me and said, we know who you are, we know you were a very close friend, and you’re our friend now. I’m actually getting emotional just thinking about it. It was just a beautiful, beautiful thing. And that’s exactly what they did, this beautiful, cosmopolitan lot – they immediately started phoning me and inviting me to parties. They just looked after me. And some of those boys and girls became my oldest friends.

I started smoking dope when I was about 13 or 14 – I was an early starter. I was invited to an all-night party after a school play and a group of us got stoned. The next day somebody grassed us all up to the school, and a massive inquest started. I attempted to fib my way out of it but eventually I crumbled under interrogation. And because the rest of them had ’fessed up very quickly but I’d held out for a couple of weeks, I was thrown out of school from early May and told they would decide later whether I would ever return. I felt very hard done by. One piece of advice I would give my younger self now would be, don’t crumble. Hold out. They could never have proved it. Instead, a couple of guys sold the story to the Daily Mail and from there it was on to the front page of the London Evening Standard. And my mum was ridden by guilt; she felt that because of her profile, what should have been a dramatic but private incident became a public one. She felt that I’d been pilloried in public because of who she was. And she was absolutely right. But it didn’t affect my relationship with my parents. We rode it out together.

Being suspended from school and then plastered across the press was traumatic. But by god it made me interesting. I had a very long, sociable summer that year. I remember it being one of the best summers of my young life. A lot of partying. But I still remember the feeling of being told by the school, as all of us who were thrown out were, that we would amount to nothing. I despised the school for that. It was a destructive and evil thing to have done. And it was also bollocks. We became journalists, senior barristers, psychotherapists, playwrights… we were all very, very successful in what we chose to do. A little while later the school got in touch to say they were writing a history and they wanted two pages on me and I thought, fuck off.

Ours was a close-knit family. But I think it’s fair to say that as the youngest child, my mother and I were very close. I got on very well with my dad but he dealt with depression through many of my teenage years, which made it complicated. There was a very interesting moment when I got my A levels and I was preparing to go to uni and my mum said, “I am so jealous of you.” I think it was that sense of, you’ve got it all to play for. She was that sort of person, she swept up everything that came her way. With her it was, give me experiences, give me more, more, more, more. She was ambitious and liked excitement and I think she totally understood what I was about to go off and do.