Naomi Klein was born in May 1970 in Montreal, Canada. Her first book, 1999’s No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies became a manifesto of sorts for turn of the century anti-globalisation movement, sold over a million copies and was translated into over 30 languages. Time magazine has since chosen No Logo as one of the Top 100 Non-Fiction books published since 1923.

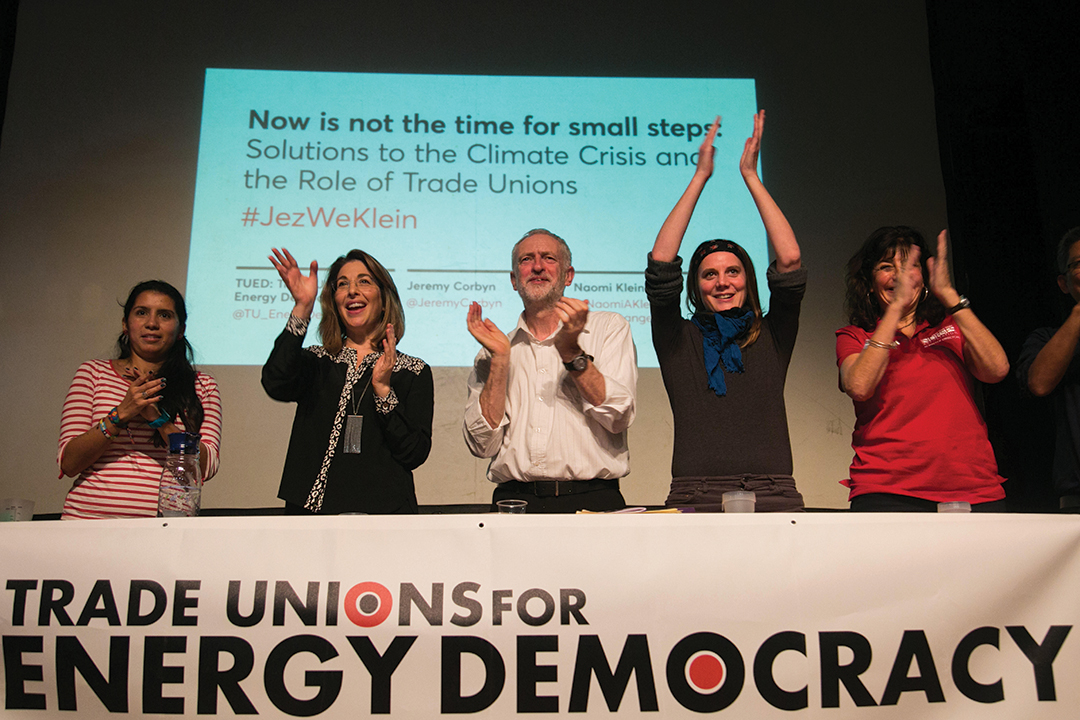

Klein went on to publish a string of best-selling books, including The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, This Changes Everything: Capitalism Vs The Climate, No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Tactics and Winning The World We Need, and On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal. In 2004, her reporting from Iraq for Harper’s Magazine won the James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism. Her new book Doppelganger finds Klein investigating her relationship with Naomi Wolf, a writer with whom she is frequently confused despite having vastly different beliefs. As Klein learns more about Wolf’s preoccupation with conspiracy theories and the alt-right, Doppelganger becomes an investigation into the way that technology has been a catalyst for the polarisation of society.

Speaking to The Big Issue for her Letter to My Younger Self, Klein looks back on a rebellious adolescence, her early impetus for becoming politically active, and the impact of No Logo.

I was a troubled teenager – 16 wasn’t my worst year, but it wasn’t my best. I was partying a lot. And I wasn’t in a good space with my parents. I was pretty erratic in school – I had certain subjects that I really loved and others that I totally ghosted. I was sneaking boys through my second-floor window. I was smoking cigarettes, a lot of them. And partying a lot, drinking a lot. Some light drugs, not too much. Using fake IDs to get into bars, lying about my age. I had pretty low self-esteem. It wasn’t a particularly happy time.

I was not at all political when I was young [despite being brought up by activist parents who had emigrated from the US as resisters to the Vietnam War, including her filmmaker mother Bonnie Sherr Klein]. You know, it was the Eighties. Stuart Hall described it as a kind of ghostly left, and I think that’s the way it felt to me. It didn’t feel very dynamic. I think one thing I understand better now than I did then is that the Eighties were very hard for my parents. They had both been very active in the Sixties and Seventies. And I think the Eighties came as a shock. North America was so depoliticised. It was so consumerist. So the conflict I had with them was mainly over me just wanting to be a child of the Eighties. What I didn’t understand was that what I perceived as personal anger towards me, was really their own political disappointment about what was happening in the world. The fact that they just had an Eighties child in me became sort of the fulcrum for that sadness and disappointment.

The last year that I had an able-bodied mom was when I was 16. The next summer a lot of things changed for me. Our whole family’s life changed pretty dramatically. My mom had two strokes. It turned out that she had been born with a brain tumour. So she had to be transported to the only hospital that could perform this very high-risk brainstem surgery to remove the tumour. And then she was in neurological ICUs for a long rehabilitation. She was hospitalised for about a year in total. Then there was a lot of caretaking. I didn’t do very well in school when my mother was sick, I dropped out of junior college because I was at the hospital all the time.