Do you remember your first train trip? I do. I was five years old in the tow of my grandmother on a three-day journey through the Canadian Rockies in coaches pulled by a steam engine. It was a short hop to a lifetime of wishing to be “elsewhere”. A song that decade bred my wanderlust. American hit The Wayward Wind reached number one on the UK chart in 1963 in a recording by Frank Ifield. Its lyrics rationalised my behaviour: “And I guess the sound of the outward bound, made me a slave to my wanderin ways.” Since then, I’ve ridden the rails in 36 countries.

More recently, I had the chance to board a westbound Rocky Mountaineer in Banff, Alberta destined for Vancouver, British Columbia. From there I’d go aboard their train heading north-by-northeast, venturing back for a spell in the Rocky Mountains. To be on one of the world’s most famous trains begged an accomplice. Spontaneously, I invited my 10-year-old grandson Riley, creating an opportunity to see travel through eyes one-seventh the age of mine.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

Meandering to the rhythm of tracks meant I could share the hidden truths of train travel with my grandson. For a start, you have unexpected peace of mind (it’s like a long walk without the footwork). There are new friends (each with a story to tell, or a secret to hide).

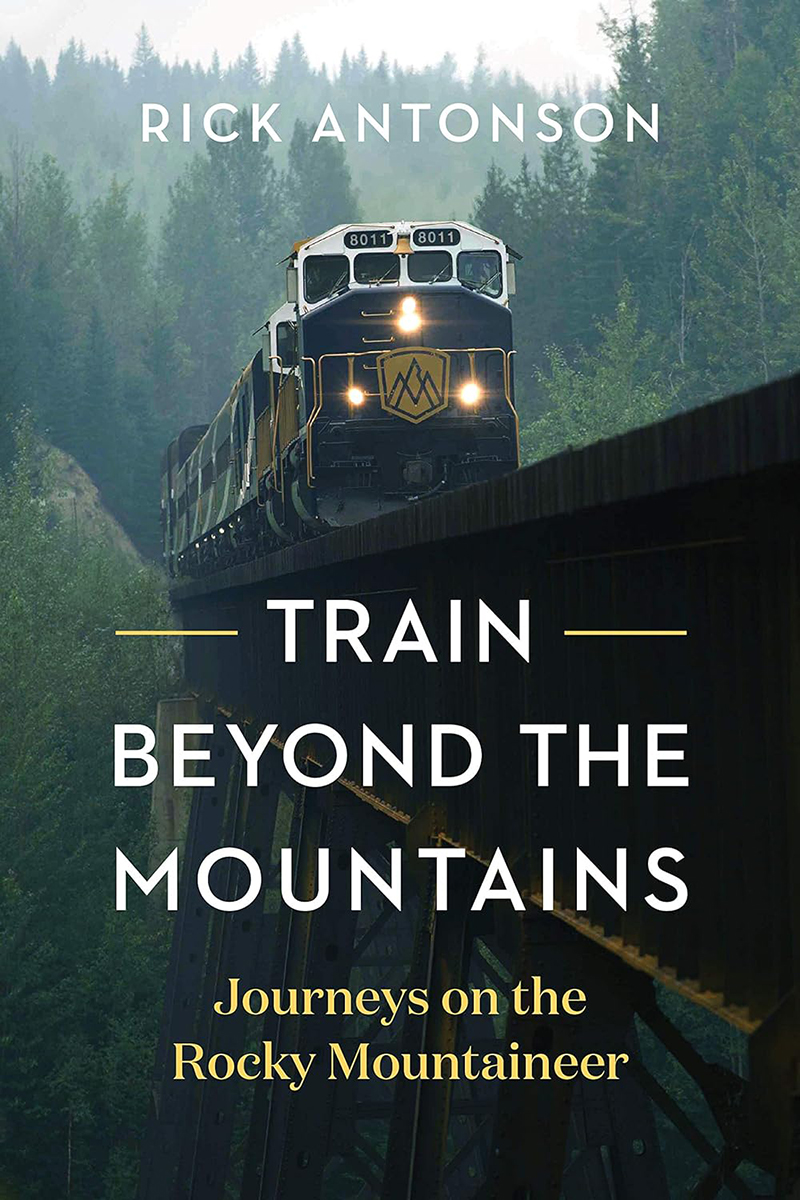

The Rocky Mountaineer’s bi-level coaches have a bowed glass roof. Every vista feels within reach. That is grand as the journey is overwhelmed with geography. Tracks cross trestles over gorges carved by plunging waterfalls. Mountain peaks chiselled by glaciers hover, emotionally brushing your shoulder.

Train travel is an ongoing moment. It is the continual unfolding of anticipation and understanding. History feels closer on a train. A smattering of facts: this Canadian Pacific Railway route built a country, its last spike driven in 1885 when Canada was threaded together as a nation, stitched with steel against the odds of political shenanigans. Onboard, Riley would ask about Indigenous peoples – among them the Shuswap, the Kwantlen, the Lil’wat – through whose unceded territory we moved. Chinese railway workers were hastily buried when they died during construction, their remains and names resurrected by researchers known as bonepickers. I love to tell readers those stories.