I came from India to Rugby in England [for boarding school] when I was 13. By 16 I was a pretty conventional public school conservative from a well-off conservative family. With one exception – I had no idea when I came to school that I would be judged as someone who was different to the others because I wasn’t English-white. It really was a harsh awakening. It gave me a difficult time in those early years. I had been happy until I came to school in England. I’ve often thought if I’d been good at games my background wouldn’t have mattered. There were a few other Indian/Pakistani boys who were outstanding cricketers and they didn’t seem to have the same experience. But I was lousy at games.

I was very worried when I went to university in England that it would be a continuation of the same racist treatment. But my father convinced me it was a very good thing to go to Cambridge. Now I’m glad he did – it turned out to be a very happy time and undid a lot of the damage of school.

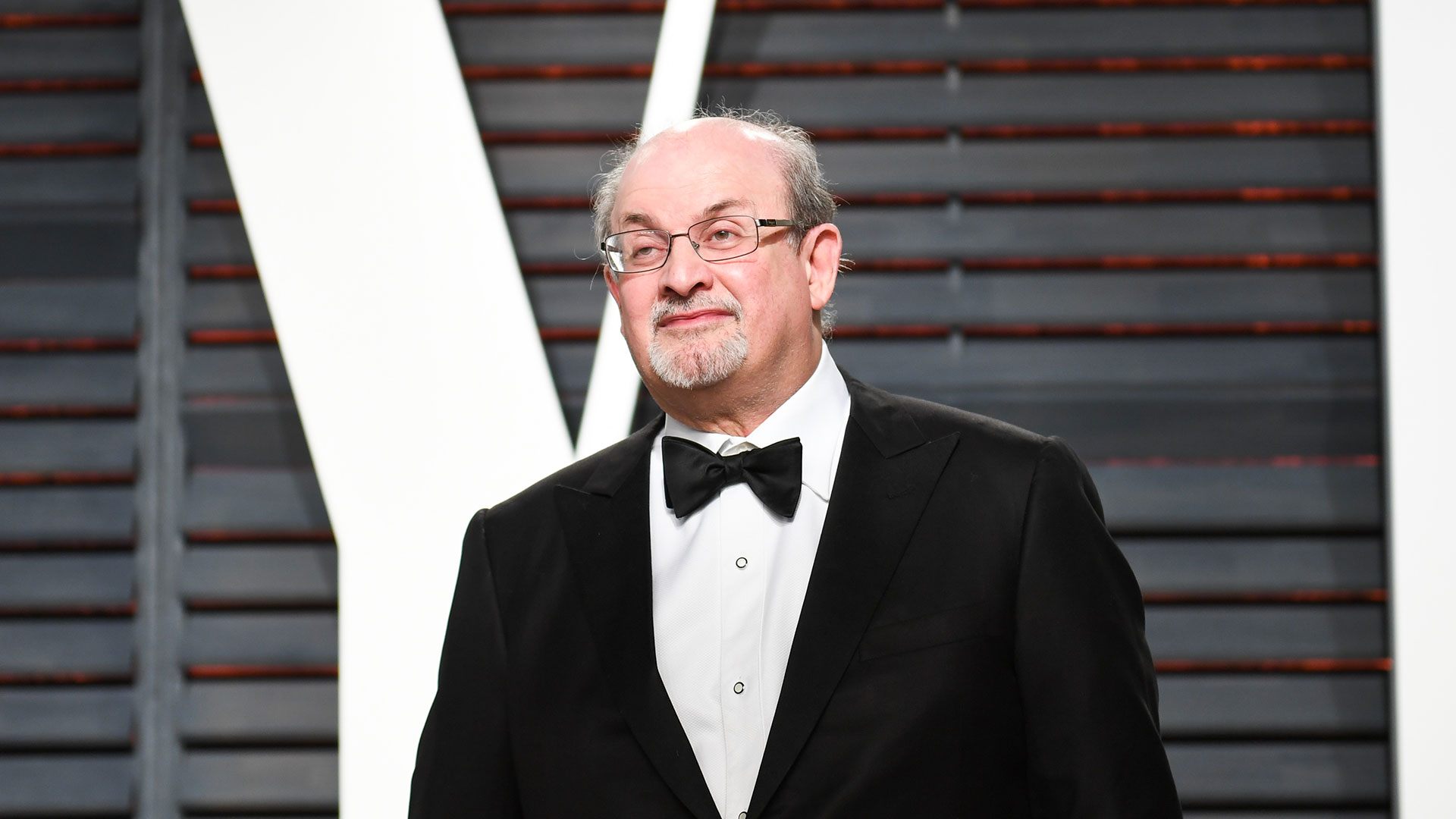

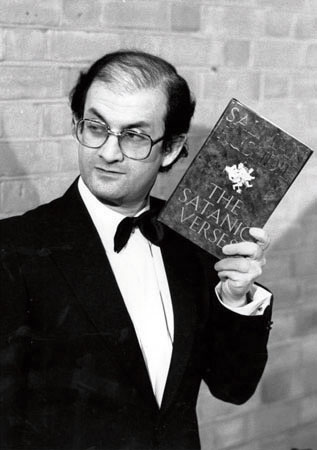

I have no regrets about writing The Satanic Verses. It’s one of the best things I ever did.

I went to Cambridge in the mid-1960s, when it was at the epicentre of that decade’s social change. It was a very good time to be 18 to 21. They were very political years, the period of protest against the Vietnam war. That was a political awakening for me. It was also the age of the counterculture. Someone called it the youthquake – young people were having an influence on society for the first time. Being part of that made me see everything – myself, my generation, the sexes, society – in a different way.

I didn’t see it then but now I recognise how much of the way I see the world came from my father. His interests have become my interests. Even my family name was invented because of my father’s philosophical interests [his father adopted the name Rushdie in honour of the philosopher Ibn Rushd]. If I could get back some of the time when my father was still alive, I’d like to talk to him about how much his ideas came to influence mine, and express my gratitude. As for my mother, I understand much more clearly now how much she gave up to send me to school, and how understanding she was, though the separation was very painful for her.

I’m actually rather proud of my younger self. He had guts and enormous will power. I left university in 1968. Midnight’s Children was published in 1981. It took me almost 13 years to find my way as a writer. I’d go back and tell my younger self, well done for sticking at it. The idea you have 12 years of your life trying to do something without any guarantee you’ll be any good or have any success. That takes tremendous desire and will.

I often wobbled in those 12 years before Midnight’s Children. I had doubts that whole time. Much of that early writing was completely unsuccessful, much of it wasn’t published. My first published novel Grimus was very poorly received – there are huge chunks of it I’d rather hide behind the sofa when I read them now. I was working part-time in advertising and my colleagues were constantly telling me not to be stupid. They told me if I focused on advertising I’d make an enormous amount of money and who did I think I was kidding? Everybody in advertising has a fantasy of writing a book or a TV show but most of them never do it. But something in me made me keep going and going.