I’d wanted to be in a group from being really, really young, probably from around eight. I used to watch The Monkees TV show and The Beatles films on Boxing Day – they often had them on then – and that just filled my head with the idea of being in a group. I was a fairly shy kid, so the idea that you could have a band who were a gang and they all lived together was very exciting to me. And eventually, by 16, I’d managed to actually persuade some people to be in a band with me.

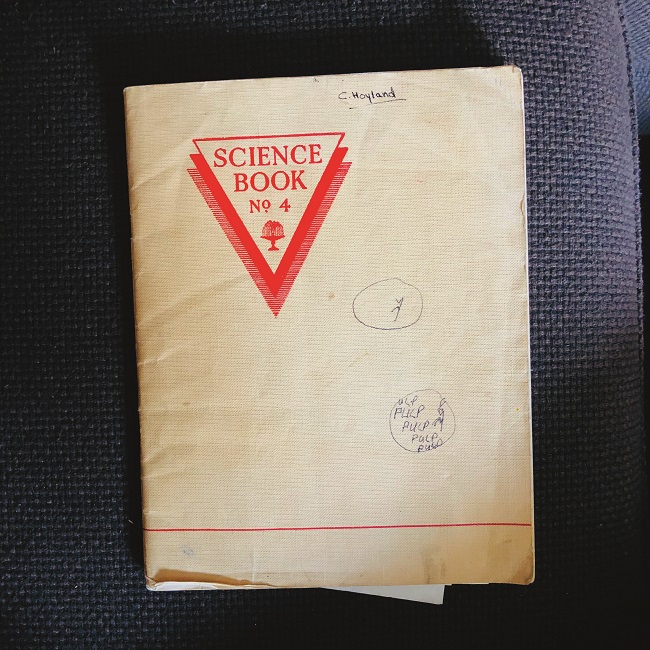

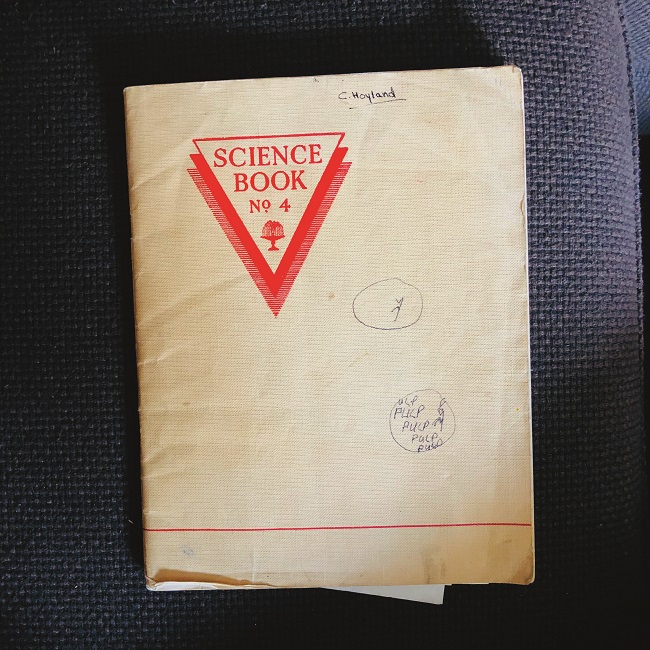

I recently came across an old school exercise book from when  I was 16, so I know exactly what I was focusing on then. It has a plan for the band Pulp – or Arabicus Pulp as we were called at first – and the first thing I talk about is Pulp fashion. It says “most groups have a certain mode of dress which is invariably emulated by their followers” – I’d obviously been reading a dictionary. “The Pulp wardrobe shall consist of duffel coats, preferably blue or black, crew-neck jumpers from C&A” – not sure why, I don’t think we had a sponsorship deal – “garishly coloured T-shirts and sweatshirts, preferably of an abstract design, plain-coloured shirts, thin ties, drainpipe trousers, pointy boots, cheap white baseball boots, Oxfam jackets, preferably with buttonholes, silly socks, hair shortish, no sequins unless for silly purposes.” I don’t know how I came up with these ideas, especially the duffel coats. I mean, they’d be too hot to wear on stage, wouldn’t they? Maybe I was imagining we’d play a lot of outdoor festivals.

I was 16, so I know exactly what I was focusing on then. It has a plan for the band Pulp – or Arabicus Pulp as we were called at first – and the first thing I talk about is Pulp fashion. It says “most groups have a certain mode of dress which is invariably emulated by their followers” – I’d obviously been reading a dictionary. “The Pulp wardrobe shall consist of duffel coats, preferably blue or black, crew-neck jumpers from C&A” – not sure why, I don’t think we had a sponsorship deal – “garishly coloured T-shirts and sweatshirts, preferably of an abstract design, plain-coloured shirts, thin ties, drainpipe trousers, pointy boots, cheap white baseball boots, Oxfam jackets, preferably with buttonholes, silly socks, hair shortish, no sequins unless for silly purposes.” I don’t know how I came up with these ideas, especially the duffel coats. I mean, they’d be too hot to wear on stage, wouldn’t they? Maybe I was imagining we’d play a lot of outdoor festivals.

The next thing after fashion is a section called The Pulp Masterplan. The first bit goes “Category A: music” – a bit formal for a teenager. Then: “Being first and foremost a musical unit, it is fitting that Pulp’s first conquest should be of the music business. The group shall work its way into the public eye by producing fairly conventional, yet slightly offbeat, pop songs. After gaining a well-known and commercially successful status, the group can then begin to subvert and restructure both the music business and music itself.” So that was the idea. I guess that must have been influenced by being brought up in the punk years, the idea that music wasn’t just a form of entertainment, that it could effect some kind of social change as well. And that’s probably why, when we did make it, it went a bit sour. Because I realised we couldn’t change the whole world. So I got a bit of a downer then.

This manifesto idea is the classic thing of locking yourself away in your room and coming up with a way of how you’re going to change the world, then when you’re out in the world, not being able to actually say any words to anybody, especially girls. I was quite awkward. I think I got my first girlfriend when I was 16. I used to have a Saturday job in the fish market, and it sounds a bit silly, but it was like, our eyes met across a filleted cod. That was exciting to me because she wasn’t a girl who went to my school. I did fancy girls at school but it was just was too nerve-wracking to talk to them.

John Peel was my first real musical compass. You read about punk in the music papers but you couldn’t really get to hear it, not on local radio in Sheffield anyway. There was a rock show on a commercial station and the DJ made a real point of saying, “You won’t hear any of that punk music on here, that’s not real music.” So I remember one night when I was about 14, just twisting the dial and I randomly came across the John Peel show. I think he was playing an Elvis Costello song. And once I discovered him that was it, the gateway was open. It was a musical education. Then when I was 17 Pulp recorded a demo in a friend’s house and I knew John Peel was doing a gig at Sheffield Polytechnic. So I went along and followed him out to the car park like a stalker and gave him this cassette. A while later, when I was at school, my grandma took a phone call from his producer John Walters. We were offered a Peel session. Well, you can imagine, it just blew my mind.

I’d tell my younger self to just chill the fuck out. Calm down. ’Cause at that age you think it’s just you who doesn’t know how to do things. And, of course, what I’ve learned in the intervening years is that everybody’s got that feeling of being an imposter or faking it. Nobody really knows how it all works. Once you realise that, you can start to relax and say, we’re all just getting through it the best we can. But I had this very strong feeling when I was young, that I was just completely inept. Maybe it was the fact that my dad had left when I was seven, so I’d never really had a male role model, no one to talk to about relationships or any of that stuff from a male perspective. I was a bit at sea. And I imagine I was some kind of neurotic nightmare to go out with.