I grew in a hippie family on a commune. My parents were raised Southern Baptist on Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, Tennessee and had broken with that tradition to move into an empty barn in the woods with a bunch of people and a parachute on the ceiling. It was supposed to say ‘Be Together’ on it, but the guy who spray painted it was really high, so it said ‘Be A Tog Eater’ instead. We had rats in our kitchen and my parents would feed them, because they were hippies and rats are people too. I think they were right about that.

My parents gave me what I needed. And it’s very difficult to give a 16-year-old what she needs for a counterculture life. They played Jimi Hendrix and Appalachian folk songs and they were right about that too. There’s very little music in the music business, so they had chosen carefully to find some purity of expression. While on the surface it all looked crazy and ambiguous as a lifestyle, I had exactly what I needed to reach 16 and be in my band. ‘Be Together’ meant you live in a van with your bandmates. I’d think, ‘I’m garbage, I am a rat… but I’m people too’. And the visceral orientation between Jimi Hendrix and Appalachian folk songs was our shared language.

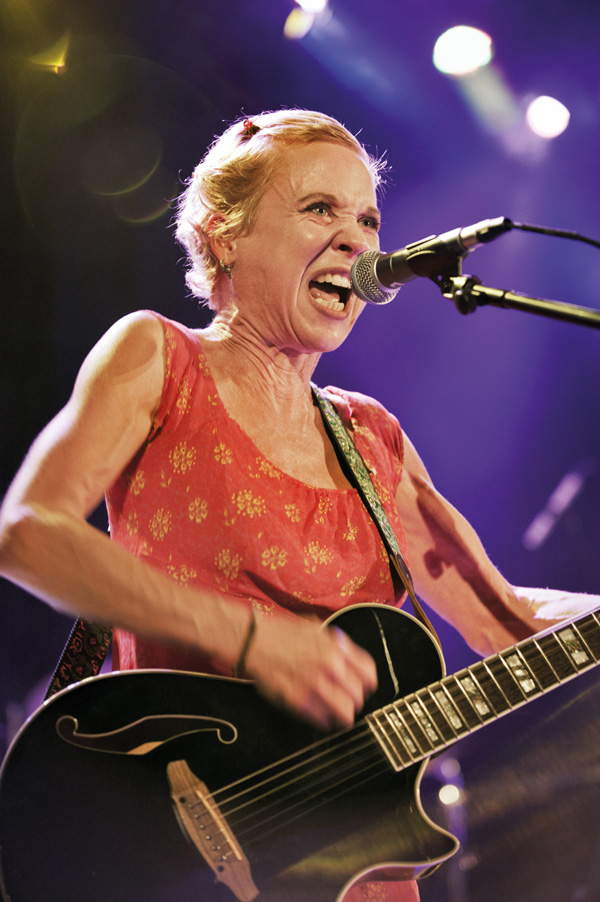

My bandmates were always protective of me. I’m very, very shy. You can see in early photoshoots that I’m always hiding at the back, barely peering around my fringe. On stage, I got to hide in noise even though I had to stand in the front and sing my songs and they were obviously autobiographical. My bandmates gave me the strength to be there at all. I would have just been lost in a room somewhere with all those colours around me if it wasn’t for them. So I was noticed because I hadn’t got the ‘cool’ memo, and then people listened. I still don’t know why. Even I find our first Throwing Muses record, which is pretty palatable compared to how we really sounded, to be unlistenable.

I didn’t find the Boston scene exciting, I am just not made that way. I’m here for focus. I found the social thing off-putting. I didn’t like that there was a scene and there was hype, although it was an extremely supportive scene where you were supposed to create your own sonic vocabulary. So there was an interest in people who sounded like themselves. We played on bills with Dinosaur Jr, and Pixies and there was no headliner. The bands would come offstage and become the audience, some of the audience would go on stage and they’d be the next band. You could play all the time, and that’s beautiful.

As a teenager, I was friends with an old movie star, Betty Hutton. I had never heard of her, because you couldn’t Google stalk someone in the 1980s, but we went to college together. I was 15 when I started college and she was about 65, so we became friends because nobody else wanted to talk to us. She would call what I did, of all things, showbiz. I was a shy dork and to me it was nothing but music – and music didn’t belong in the public sphere. It’s like spirituality versus televangelism. Betty was interesting because she brought her humanity to an extremely shallow industry. She said, why would you play a song out loud instead of keeping it in your head? I would say, because I’m addicted to the guitar – but I’m not going to encourage people to listen by wearing lipstick!

The hardest part for me was getting trapped on a major label. I knew you shouldn’t engage with something this greedy, this shallow, this exploitative, but it happens. You’re advised you will bring quality to their quantity, so you begin with this enthusiasm. You say, here is some substance. But they bank on the assumption that people are stupid – and I kept fighting for the right to not make that assumption.