My childhood was horrible. I am a war baby, born in 1944. My mother was in the Women’s Royal Air Force and was a very clever working-class girl from east London. She met a Canadian officer and I was the result. It really fucked up her life. She was on a fast track to become an officer in the RAF and they threw her out because she was pregnant. Her father wouldn’t let her keep me. The poor darling tried to get an abortion, which was then illegal. And I don’t blame her.

When I was seven my mother said to me, ‘I wish we had not adopted you’. Something I totally agreed with

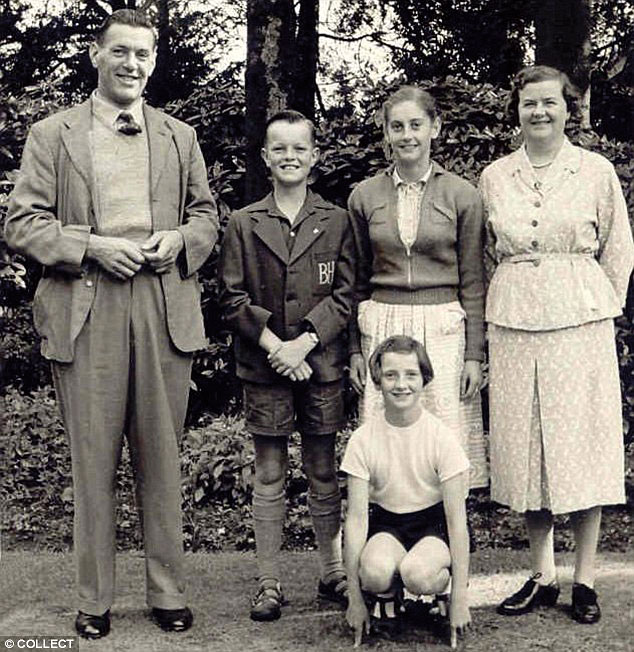

I was adopted by a family who belonged to a fundamentalist evangelical sect called the Peculiar People. And they were. There were millions of things they disapproved of – it became a sort of wish list. They disapproved of television and I ended up working in TV. They disapproved of military service and I ended up writing about Sharpe. They disapproved of alcohol, I love my whisky. They disapproved of nicotine, I’m a smoker. I remember my father frowning terribly at some blonde in high heels – and I married one. They had the good puritan suspicion of fiction and I became a novelist. You could say I rejected their doctrine.

When I was seven, my mother said to me memorably: “I wish we had not adopted you.” Which was something I totally agreed with. What saved me is that they sent me to boarding school because the local school wasn’t religious. In my teens I began to realise there was a world outside the Peculiar People. They thought it was a mistake, they should have kept me at home and kept on thrashing me. My hopes were just to escape. It was a curious childhood. I never saw a film until I was 14. But I had started reading the Hornblower books and thought being a writer sounded better than working. And so it has proved.

If you were brought up to believe you have to give your heart to Jesus, you believe that crap for a long time. I became a serial heart donor for Jesus but it didn’t take. At university I realised all those things they disapproved of were waiting for me. I was on the King’s Road, Chelsea, in the early ’60s and made up for lost time. If you wish to use the word swinging, I suppose you can. But now I am a respectable married man, so I don’t recall it!

I didn’t begin to grow up until I realised my parents were not responsible for my unhappiness. I was. At that point, you take control of your own life. Oh gosh, I sound like a self-help book. I don’t want to make it sound too bad, I’m fine. Don’t waste any pity on me. But if you blame your parents for your misery, they can blame their parents and we eventually load the whole damn lot on Adam and Eve.

If you were brought up to believe you have to give your heart to Jesus, you believe that crap for a long time.

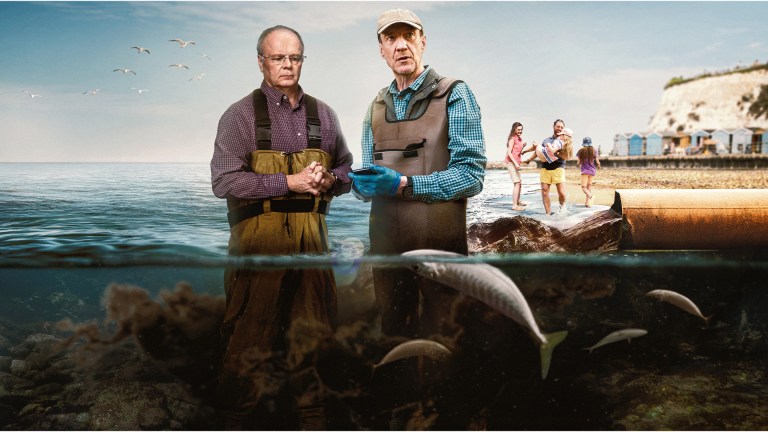

I was in Belfast from 1978 to 1980 and had a very young trainee working for me called Jeremy Paxman. I’d love to know what happened to him. Joining the BBC was an extraordinary break from my childhood. I worked on Nationwide, which was on live, five nights a week with audiences of 14 million, before becoming head of current affairs for the BBC in Belfast. I loved it. The Troubles were at their worst but everyone seemed born into the comedian’s union.