So it’s important to get your facts straight. To help, we’ve cleared up six common questions and misconceptions about workers going on strike.

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription

1. Workers aren’t paid to go on strike

Employers can deduct pay from their employees’ wages for the time they spend on the picket line. So if someone goes on strike for one week, they can expect to lose a week’s pay.

Most unions have hardship funds to support their members who suffer a particularly large financial hit by participating in industrial action. Some unions offer a small allowance to members who are on strike to help cover their daily costs – sometimes referred to as ‘strike pay’ – sometimes around £70 a day.

But it’s not true that workers are paid when they are on strike.

2. Union leaders are not ‘barons’

Each union is led by a general secretary and president who are elected by members of the union. The Department for Business, Energy Innovation and Skills lays out how unions should elect their executive body, including being subject to independent scrutiny of their elections.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Tabloids have taken to calling union leaders “barons”, which has connotations of nobility. Critics say it’s an attempt to paint leaders as unaccountable and suggest they are in a higher economic class than their members. But they are elected by members of their union.

3. Salaries of workers going on strike are often below the national average

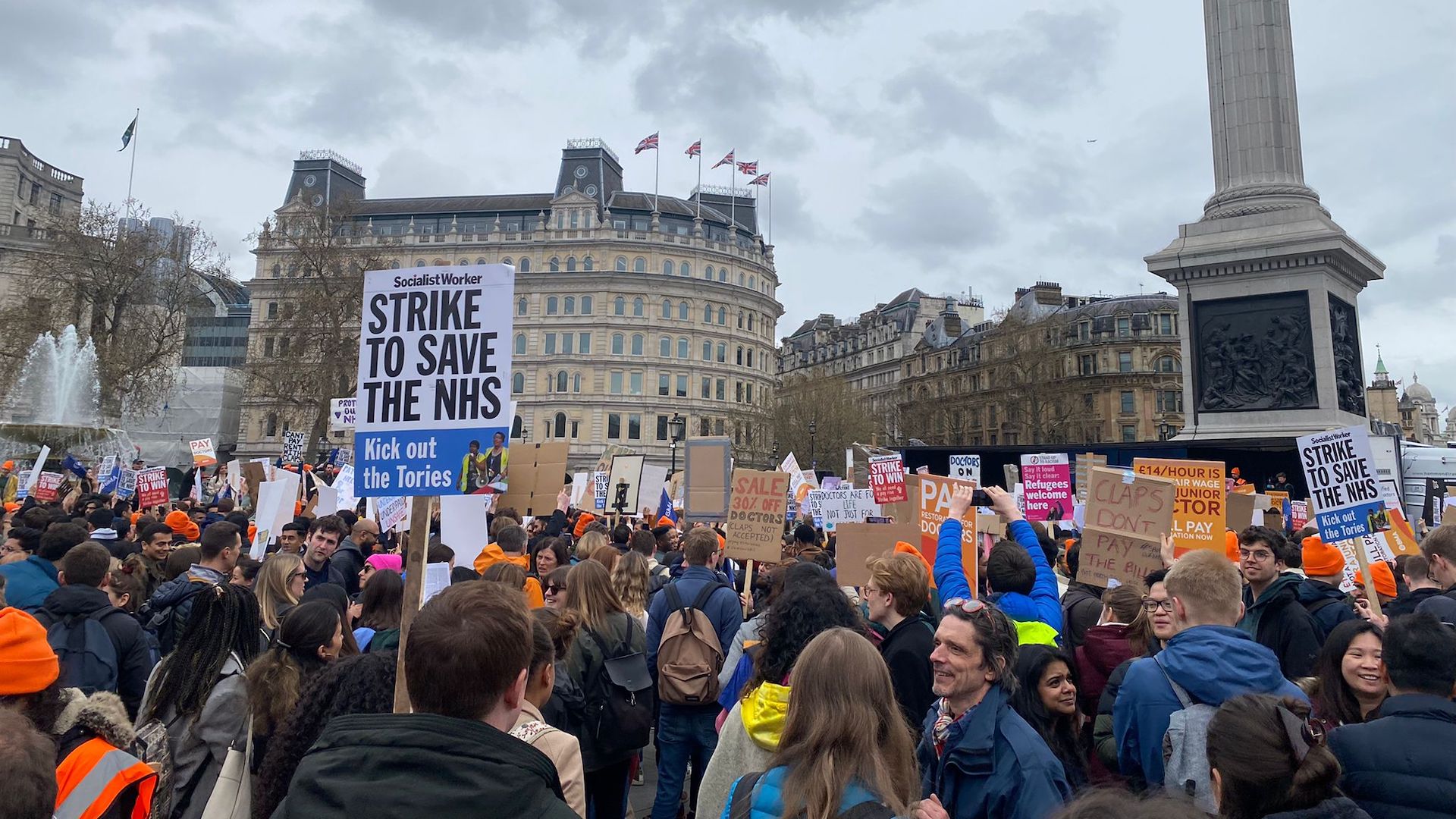

How much does a junior doctor earn? Misinformation is rife when it comes to the salaries of workers going on strike.

Junior doctors are calling for a 35 per cent pay rise which would restore their pay cheques to what they were worth in 2008, according to the British Medical Association. With pay not keeping pace with inflation for over a decade, many junior doctors are paid just £14 an hour.

While completing their first two years of training, junior doctors are paid £29,384 to £34,012 per year, moving up to £40,257 in year three. However deductions for student loans, tax and an NHS pension means many see around £1,000 a month docked from their take home pay.

“There are doctors in their first year of work following medical school, graduating with £80-£100,000 of debt, who are being paid £14 an hour,” Ada Zembrzycka, an anaesthetist at Whipps Cross Hospital in east London told The Big Issue.

“And they are fully trained, fully qualified medical professionals who prescribe life-saving medications like really strong antibiotics in the middle of the night for patients who need their help the most who are there, often the first doctor to see a person whose heart has stopped and tried to restart it.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

And when it comes to other industries engaged in industrial disputes, the average civil servant who is a member of the PCS union was paid a £23,000 salary in 2022.

For comparison, the average Brit made £31,285 in the year ending April 2021.

Although the number one demand from workers on strike is usually about pay, this is rarely the only demand. Striking workers are often also protesting for better safety measures in their workplace or against the threat of job cuts.

4. A picket cannot stop people going to work

A picket line is essentially a demonstration of workers outside their workplace to tell other people that they are participating in the strike. People on the picket line seek to encourage others to join them, encouraging customers or colleagues not to enter the business or organisation in solidarity.

The law protects peaceful protest, but people on picket lines are subject to the same rules around anti-social behaviour as anyone else taking part in a demonstration, which bans intimidation and harassment.

“In no circumstances does a picket have power, under the law, to require other people to stop, or to compel them to listen or to do what he asks them to do. A person who decides to cross a picket line must be allowed to do so” states the BEIS code of conduct on picketing.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

The government recently changed the law to allow businesses to hire agency workers to replace striking workers. Unions have branded the move an attack on the right to strike and raised concerns over the safety of bringing in temporary staff to work roles that require high levels of skills and experience.

5. Strikes don’t always make workers less popular with the public

It depends on the strike, with different sectors getting more support than others. A July poll from YouGov found that Brits are most likely to support nurses, doctors and firefighters going on strike. For each of these jobs, a majority of those surveyed would be supportive of the choice to strike.

But in the same poll the sympathy didn’t go as far as barristers, civil servants or lecturers. Three in 10 people would back a strike by university staff, and only 27 per cent would support striking civil servants.

Despite their desperation for more funding, striking barristers were supported by a mere 19 per cent of Brits.

The train strikes have been the highest-profile of the year and the public has generally been divided. Around 35 per cent of Brits quizzed by pollsters Ipsos in June said they supported the walkout, while the same percentage said they oppose it.

A more recent poll from Savanta ComRes suggests that support has grown, with almost half of all UK adults saying they would support rail workers going on strike over pay and conditions, with a third saying they would be opposed.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

6. There won’t be a general strike

A general strike is politically motivated action which would see people across different sectors, and members of different unions, all go on strike at the same time with a shared vision for change.

The mass strikes that took place on 1 February saw up to half a million teachers, university staff, civil servants, train drivers and other others take to picket lines and protests across the UK.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

It wasn’t a general strike, but trade unions historian Dr Edda Nicolson told The Big Issue it was “the most important coordinated action we have seen since the 1926 General Strike”.

The last general strike took place in 1926 when up to 1.7 million people refused to go to work to show solidarity with striking miners but legislation introduced in the 1980s banned “sympathy strikes” which take place when a union instructs its members to go on strike in support of another.

This means only a union engaged in an active industrial dispute with an employer which has taken a legal ballot of its members can call a strike among its members. No one union can call a general strike – or sympathy strike – across the UK or across industries. Not even the Trades Unions Congress, the federation of trade unions.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty