“It is important to remember that these are seasonal workers — men and women who come here to work, pay tax and National Insurance in the UK, contribute to the rural economy and then go back to their own countries at the end of the picking season.”

The job is tough and physical. There are early starts – shifts run from 6am to 3pm with breaks. In current heat a 45-hour week can look long.

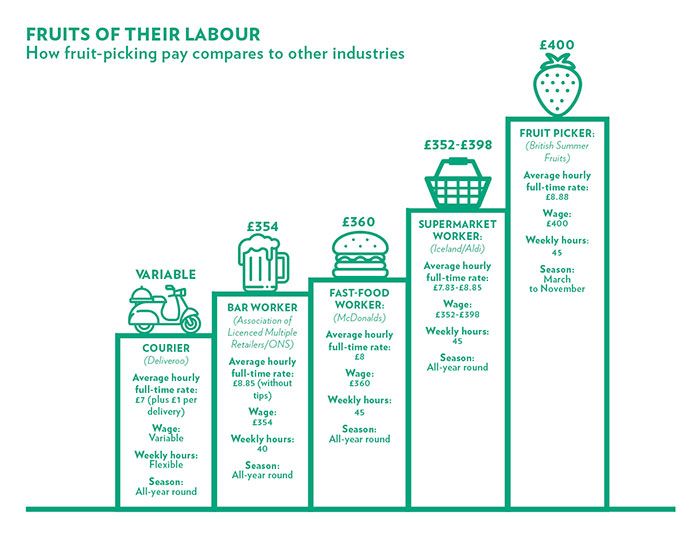

But the pay on offer does not conform to type, with pickers typically earning on average between £400 and £450 per week – just above minimum wage – while the highest earners take home £675 with bonuses.

If it’s not money stopping people from the UK doing the work, what is it?

Paul Kelsey runs Kelsey Farms in Wickhambreaux, near Canterbury, and he believes that the British ideas of fruit picking need to change if there is to be a return to the Eighties when he used to put on a double-decker bus for local housewives to do the job.

“At the minute, we are doing okay for workers. Is it an ongoing problem? Yes. Are we thinking about how to work around it? Yes. It’s front and centre in our thoughts,” he says.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“If you look at British society, it’s very far removed from farm work and rural life and there is a perception that it is work that is not worth doing – there is a disconnect when it comes to farming.

“We’re in soft fruits and they are a perishable product – they need picking and they need to be picked every day otherwise you lose your product and not just a bit of it, you lose the whole lot.

“There is also a perception that if you come and do temporary work for us then you have to come off benefits and it can be difficult to get back on once you’re done. It is a long and arduous process to get back on and that can put people off when they can go into a town and get a permanent position in a high-street store.”

If you look at British society, it’s very far removed from farm work and rural life and there is a perception that it is work that is not worth doing – there is a disconnect when it comes to farming

The consequences of failure to fill the labour gap are clear – pay will have to rise and to meet that prices are going to have to go up. The Andersons’ Brexit & Seasonal Labour Report estimates that a 400g punnet of strawberries will increase by 35 per cent, costing £2.75 instead of £2. The £2 price point has remained constant over the past 20 years – a 1.39 per cent cut with inflation – as soft fruits have moved from a luxury to a staple product. If the supply chain continues to absorb a price rise then it will be felt in the pockets of producers; experts warn that it will also be passed on to consumers.

A rise would be felt by the country’s poorest, driving them towards cheaper processed foods and doing little to tackle obesity and the associated costs to the NHS. As Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City University of London, puts it: “Low-income families will bear the brunt of Brexit.”

A robot solution

If British workers can’t be enticed into the fields then robots could offer another way. Belgian start-up Octinion has already trialled their robotic arm in the UK, while Cambridge’s Dogtooth has experimented with the technology in Australia, although its benefits are still to be seen.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

The influx of foreign workers in the industry is by no means a new phenomenon. Irish migrants are known to have worked in the industry as far back as the 14th century while the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS) introduced in 1945 after World War II left the workforce seriously short. Initially, it attracted workers from the Soviet Union but by 2008 it was only open to workers from Bulgaria and Romania. When freedom of movement restrictions were lifted across the EU in 2013, the scheme was ended.

If solid proposals are not in place before we leave the EU next March, an industry which is worth millions to the UK economy will wither on the vine

So far, nothing has taken its place, with the government only offering assurances that European workers can be recruited until December 2020 alongside a Future for Food, Farming and the Environment consultation that ended in May. Another report by the Migration Advisory Committee is pencilled in for the autumn.

Environment Secretary Michael Gove told the National Farmers’ Union that the case for a new SAWS was “compelling” earlier this year after president Minette Batters warned that the industry will see “veg rotting in the fields” without it.

But the campaign for SAWS to be replaced post-Brexit remains top priority.

“Politicians are making lots of positive noises, but the time for talk has long passed,” warns Marston. “What we need now is action and clarity on SAWS as a matter of urgency. If solid proposals are not in place before we leave the EU next March, an industry which is worth millions to the UK economy will wither on the vine.”

Image: Getty