I grew up wedged between two sets of brothers – two older than me, two younger. Five of us born in six years. So by the time I was 16 I was a tomboy, and I had a strong sense of equality and justice. My brothers always claimed I was the favourite. My parents made it clear that they wanted me to have the same opportunities as my brothers, but the wider Irish society in Mayo didn’t give me that same sense. I had very few options. I was expected to marry very young – which I had no interest in doing – or become a nun. I was quite religious in those days, my family were very religious. And we had nuns in the family who had lived very full lives off in England and India. When I finished boarding school I told the Reverend Mother I wanted to become a nun. But luckily she told me to go away for a year and think about it. My parents were so pleased with me they sent me to Paris for a year. Of course, that changed everything and I came back wanting to study law.

I adored my father, he was a wonderful doctor, a vocation doctor. I used to love going out with him on evening house calls. He’d tell me stories on the way there, then he’d go in, leaving me reading in the car. Eventually he’d come back out of these poor, peasant houses with no electricity, and I watched him stand in the dim light of the front door talking to the mother of the house. He was bent over listening very patiently.And I waited and waited, wanting him to come back and tell me more stories. But he would stand there for 20 minutes, because he knew that listening was very important as a doctor. I think it was because of him I called my memoirs Everybody Matters, because he firmly believed that. And I grew up believing it too – no matter how poor, how old, how inarticulate – everybody matters.

My mother died very suddenly of a heart attack. It was a terrible loss to me. She only saw two of her grandchildren, including my eldest daughter Tessa, who was named after her. Then she died two days after Tessa’s first cousin was born. My mother was the life and soul of the family, the heart of the family. She influenced me more than I knew. When I was campaigning to be President of Ireland I realised I’d have to let people get to know me. I’d been very private before that, I was a naturally shy person. But the more I really talked to people on a personal level – opening up, becoming more people-friendly, warmer, a better listener – the more I became like my mother. That changed my approach to public life and I’ve never gone back.

I grew up believing it too – no matter how poor, how old, how inarticulate – everybody matters

I went to Harvard law school in 1968 after I graduated from Trinity. That year made a huge impression on me. American law students were trying to avoid the draft and condemning what they called the immoral war in Vietnam. I was impressed by their idealism, seeing young people who were determined to do things, to really make a difference. That was very different from the Ireland I was used to. Young people waited their turn. Then you were 30, and you still waited your turn. Then in your mid-40s you might be allowed to take a role with some responsibility. That’s why, when I came back to Ireland in 1969, and there was a Senate election, I queried why the candidates were always elderly male professors. And my colleagues said, if you feel so strongly, why don’t you go for it yourself. I very much stood out as a young woman of 25, arguing that we had to open up Ireland, and liberalise the country.

- John F Kennedy wins the US Presidential election

- The Domino’s Pizza chain is founded

- Eddie Cochran dies in a car crash aged 21

If I was to give my younger self advice, I’d tell her you can’t change things too quickly. The first thing I did when I was elected to the Senate was to pen a bill to legalise family planning. I was denounced in newspapers and churches. Nick (her cartoonist husband) burnt the hate mail I got. The archbishop in Dublin sent a letter to be read out in every diocese in Dublin saying the bill I was proposing would be a ‘curse upon the country’. That was very heavy for me. It caused me to really wobble. I appreciate much more now that if you want to make changes regarding things like sexual morality, which run very deep in society, you have to take time to bring people with you. You have to educate, persuade, talk to people, have patience. We did eventually get the bill through but it took nine years. It was an important lesson I took with me when I became UN High Commissioner for Human Rights [in 1997], and had to tackle harmful traditional practices in other continents such as early child marriage and female genital mutilation.

If I could have one last conversation with anyone it would be with Nelson Mandela. He was the most extraordinary person I ever met and I was so proud when he chose me as one of his elders. I wish I’d had more time with him, and learned from his incredible humanity, his gentleness, his ability to forgive. His humour too – he was a terrible tease. He used humour to stop you from putting him on a pedestal but you couldn’t help doing it anyway, he was so impressive.

I remember my father more than once coming back from delivering a baby, and telling my mother he’d been asked, “Doctor, is it a boy or a child?” He said, “I am so furious.” That convinced me that my father did think I was equal to my brothers. But the school didn’t, the wider society didn’t – I couldn’t be an altar boy or a priest. I learned very early in my lawyer’s life about the Magdalene laundry women. I heard a lot of stories about mothers literally having their babies grabbed from them by priests in the hospital. I also learned how single mothers had been treated because I was asked to be president of Cherish, the single mothers’ organisation. I so admired those women. They were treated as criminals, as fallen women, but they had plenty of fight in them.

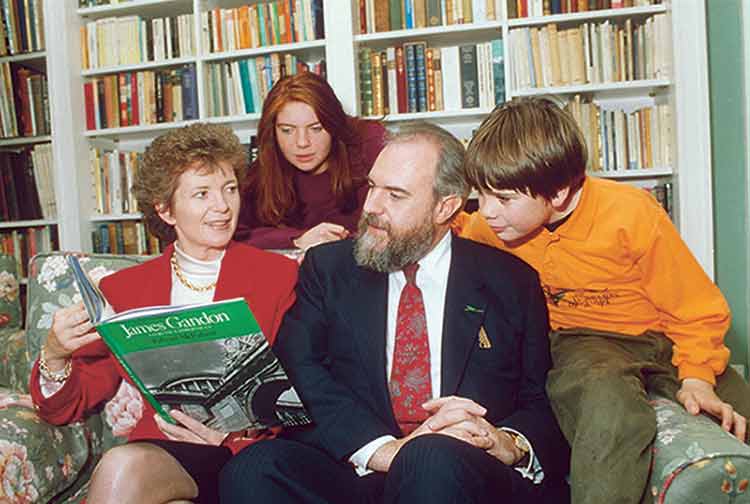

It was always important to me that my children knew they were the most important thing in my life. I remember the night I was elected President. There had been a huge celebration party. When we got home I got the three of them together and told them, even though I will now be President, you are more important. I had no doubt that, as a mother, I felt I had to say that to them. And that I meant it. There were times it was hard. I remember a long trip to India, an important state visit for Ireland, and my daughter had her birthday when I was there. I felt very far away from her. I still have a very busy life but I was very happy to become a granny. I have six grandchildren now. It gives me energy when I’m fighting to tackle the future effects of climate change, thinking of the kind of world my grandchildren will grow up in.

Mary Robinson presents climate change podcast Mothers of Invention with Maeve Higgins, available now mothersofinvention.online; Climate Justice: Hope, Resilience, and the Fight for a Sustainable Future by Mary Robinson (Bloomsbury, £14.99) will be published in October.