I became politically aware when I was 10, taking newspapers round in the Second World War. I read every one. I remember having an argument in my teens with one of the lads in my street, saying: “The Queen doesn’t have blue blood, don’t be so daft.” They thought royal blood was a different colour. I remember pointing out to them Santa Claus seems to favour rich families. So even then I was developing a political ideology. I always try to tell people – they might not know it but they’re talking about politics every day.

We were a family of nine children. I won a school scholarship when I was 10 but I used to play football and cricket with lads who were already working down the pit, so I just followed them. I didn’t think about how I might be good at representing other people until, like my father before me, I became a union delegate. I was re-elected many, many times. So when I came to parliament, that was the only kind of man I wanted to be, someone who actually believed in speaking for the people who elected me in the place where I live. That was my background and that’s how I was shaped. I have no intention of betraying those people. I told the MPs, I don’t want to be Father of the House. I told them that years ago. I don’t want to be appointed to any position, I’ve been democratically elected to every position I’ve ever had.

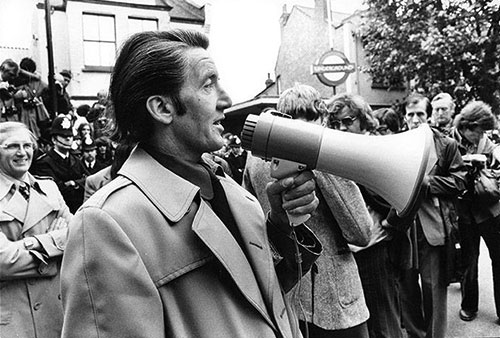

I have no intention of betraying the people who elected me to represent them

A lot of people say but what has he actually done? Well, in 1987, I probably did the best thing I’ve ever done in parliament. I single-handedly killed off Enoch Powell’s attempt to ban stem cell treatment. His bill had floundered in committee but he’d been given a second chance to get it through in the Commons. I did my research about Commons protocol and realised I could stop him even talking about his bill if I moved a writ before he was due to start. So I filibustered, talking about the Brecon and Radnor by-election for three-and-a-half hours, and by half-past two Powell hadn’t been able to open his mouth. He came up to me afterwards and said: “I reckoned without you, Skinner.” Now whenever I hear of another life saved by stem cell treatment, I know that though I was just a backbencher, I did something very important.

The other thing I’m proud of is getting my mother to sing. She got dementia in the late 1980s. She didn’t remember my name. I’d read that people who stutter don’t stutter when they sing. I thought, I wonder why? It must come from a different part of the brain. I was just guessing but one day when I was with her I started singing the old songs she used to sing when I was growing up. [He breaks into song] “If those lips could only speak, and those eyes could only see…” I thought, if she remembers this, I’ve cracked it. By the time I got to the second line she joined in. I told the family and my brother said: “I’ve never heard such rubbish.” So I got them to sit her beside the radio when I was on Desert Island Discs, I got Sue Lawley to play that song, and she joined in. After that I went to sing in the care home in Bolsover and they started an early dementia singing class. And now it’s spread like wildfire around Britain.

I can’t prove it but I know the BBC made a decision to stop putting me on TV. I used to be on Question Time every year. Then in the late ’80s, I think it was suggested to the BBC that I didn’t represent the parliamentary Labour Party. Which I didn’t. And I’ve never been asked since. Later I was asked to be on the BBC’s early-morning Sunday show to go through the papers and Andrew Marr phoned me up and said: “I’ve just heard you’re going to be on my show… well, we’ve changed the business.” That’s what he said. So I’ve never been on that. Though I used to be on Breakfast with Frost quite regularly.

I’ve seen all of Woody Allen’s films. My favourite changes all the time… Hannah and her Sisters, Play It Again, Sam, Annie Hall. Midnight in Paris was a very good recent one. With that Welsh lad, Michael Sheen. He’s a bit on the left you know. It’s about the humour. I think when you’re speaking politically you have to keep your audience with you. When I was about 10 my dad started taking me to meetings to hear people speak. I remember after one meeting in Clay Cross I said to him: “Well that man could talk, Dad.” And he said: “Make ’em laugh, make ’em cry, make ’em think, and send them home happy.” I’ve often thought as I’ve got older, if I’d been brought up in the city, there would have been a drama class somewhere and I could have joined in for all I know. I could have sung too. I’ve often thought about it.