So, what does inflation actually mean for you? We break down everything you need to know about whether the cost of living crisis is ever actually going to come to an end.

What actually is inflation? And what does it mean for me?

The term “inflation” is the technical way of describing the rate at which prices are rising. But what does it actually mean and how does it impact your life? If you’ve noticed the cost of a bunch of bananas or a pack of loo rolls is still getting pricier and your household bills are still expensive, that’s because prices are still rising. Inflation was ludicrously high for, well, far too long, and prices haven’t come down since.

The higher the inflation rate, the faster your bills increase. The inflation rate of 3.4% in December 2025 means prices rose by 3.4% on average in comparison to December 2024. Prices are still increasing and will continue to as long as inflation is in positive figures.

If you want to see just how much more expensive your shopping basket is going to be as a result of inflation, you could use a price comparison website like Trolley. It has a grocery price index with data showing how much all your basic supermarket items have increased in recent months.

Will prices in the UK ever come down?

The simple answer is that UK prices across the board will probably never come down – and almost certainly not by very much – but wages are supposed to keep up with rising prices to make us less likely to feel the pinch.

For prices in the UK to fall, inflation would need to go into negative figures, often called deflation. That is a rarity. The last time this happened was in 2015 when prices fell by a grand total of 0% because of a sudden drop in the price of oil.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

But the reality is that the 0% inflation rate was “actually quite a bad thing”, economists have told the Big Issue. It meant that the economy was stagnant and it was used as political cover for austerity.

Before that, the last sign of deflation was in 2009, during the global financial crisis, but economists disagree on the details as only one measure of prices was negative. You have to go back to 1960 to find another example of deflation.

But don’t panic. Prices will stabilise and grow more slowly and real wages should catch up, and significant progress has been made.

When will the cost of living crisis end?

The cost of living crisis is, in theory, over once prices stabilise and wages have risen enough to match. Wage growth is now above inflation and has been for some time, but we are still reeling from the impact of the cost of living crisis.

Annual growth in employees’ average regular earnings, excluding bonuses, was 4.7% in the three months to November 2025 – which is the most recent period for which figures are available. But in real terms, when wages are adjusted against inflation, growth has been slow.

Annual wage growth in real terms was around 1% in the year to January 2026. So technically, we’re getting richer than we were last year, but only ever so slightly. You probably won’t notice the difference.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Director of the Work Foundation at Lancaster University Ben Harrison previously said that a record number of people are being pushed into taking on second jobs – “often with precarious pay and uncertain hours – to try to make ends meet”.

Meanwhile, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) estimated last April that, had wages grown at trends prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the average worker would be over £14,000 a year better off.

Most people have faced a large drop in living standards. The financial year 2022 to 2023 was the largest year-on-year drop in living standards since ONS records began in the 1950s – and it will take time to recover from that.

Chris Belfield, chief economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, previously said: “Prices remain far above pre-pandemic levels as inflation remained persistently above target throughout 2025. This has driven up the cost of essential goods while employment has remained lower than before the pandemic. Meanwhile, more people are looking for work with unemployment figures up to pre-pandemic levels and real earnings are barely growing.

“As things stand, incomes are projected to continue to fall in real terms. The hope for low-income households is that the government will take significant policy action to boost incomes, productivity and earnings.”

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicts that real household disposable income – and consequently our living standards – will grow by an average of just over 0.5% a year until 2029.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Belfield added: “Scrapping the two-child limit and steps to reduce energy bills were the right decisions in last month’s budget. But JRF projections show incomes will fall significantly by the end of the parliament once housing costs are considered.

“And, of course, there are some highly significant knock-on effects from this – falling living standards are reducing spending, undermining productivity and placing huge pressure on the NHS.”

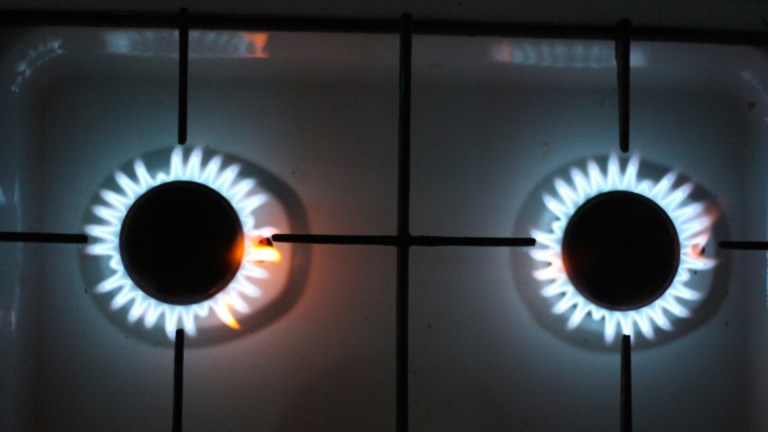

Will energy bills come down?

Energy bills rose very slightly in January 2026. Ofgem’s energy cap means average households are now paying an average of £1,758 each year for their electricity and gas from January.

That’s up from £1,755, which was the energy price cap set by Ofgem in October to December.

Every three months, the energy regulator reviews and updates the price cap to reflect changes in the cost of energy and inflation. It’s intended to ensure bills are fair.

But it doesn’t mean that your household bills can’t exceed £1,758 – some households will pay more and others less. It all depends on how much energy you use, as well as your circumstances like where you live and the energy efficiency of your property.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“The price cap does not protect those who simply cannot afford the cost of keeping warm,” Adam Scorer, the chief executive of National Energy Action, previously said. “That requires direct government intervention through bill support, social tariffs and energy efficiency.”

The government’s energy rebate scheme, a discount on household energy bills, ended in March 2023. This had been a lifeline to many people, helping them save around £66 each month.

Simon Francis, coordinator of the End Fuel Poverty Coalition, said: “Three years of staggering energy bills have placed an unbearable strain on household finances up and down the country. Household energy debt is at record levels, millions of people are living in cold, damp homes and children are suffering in mouldy conditions.

“Everybody can see what is happening in Britain’s broken energy system and it is time for politicians to unite to enact the measures needed to end fuel poverty. This includes cross-party consensus on a long-term plan to help all households upgrade their homes and short-term financial support for households most in need.”

Are prices rising at the same rate for everyone?

Unfortunately not. Prices are rising even faster for poorer households. This is because the costs of essentials like food were soaring at high rates, and low-income families typically spend a greater proportion of their income on these items.

The Resolution Foundation has found that poorer families are most affected by surging food prices as they spend a far greater share of their family budgets on food (14%, compared to 9% for the highest-income households).

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

As a result, the effective inflation rate for the poorest tenth of households is around 2% higher than it is for the richest tenth of households.

Benefits are not stretching far enough to help those on the lowest incomes afford the basic essentials – and last September’s rate of inflation meant that benefits only increased by 1.7% in April 2025.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimates that universal credit falls short by around £120 every month of the money people need to afford the essentials.

The standard rate of universal credit will increase by 6.2% in April 2026, but the foundation still estimates that it will fall short by around £1,000 each year for a single person.

JRF has consistently called for an ‘essentials guarantee’ to be implemented in universal credit – so that benefit claimants can afford the basics they need to survive at the least.

It finds that 60% of low-income families are going without essentials – equating to 7.1 million households. It’s been seven million or above for four years.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

More than half of low-income households have gone without heating, and over five million have cut back on or skipped meals.

Nearly four million low-income households have been forced to borrow to pay for food, heating and priority bills – and 70% of them have fallen into arrears.

JRF modelling projects low-income families will face an unprecedented fall in incomes after housing costs.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more.

Change a vendor’s life this Christmas.

Buy from your local Big Issue vendor every week – or support online with a vendor support kit or a subscription – and help people work their way out of poverty with dignity.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty