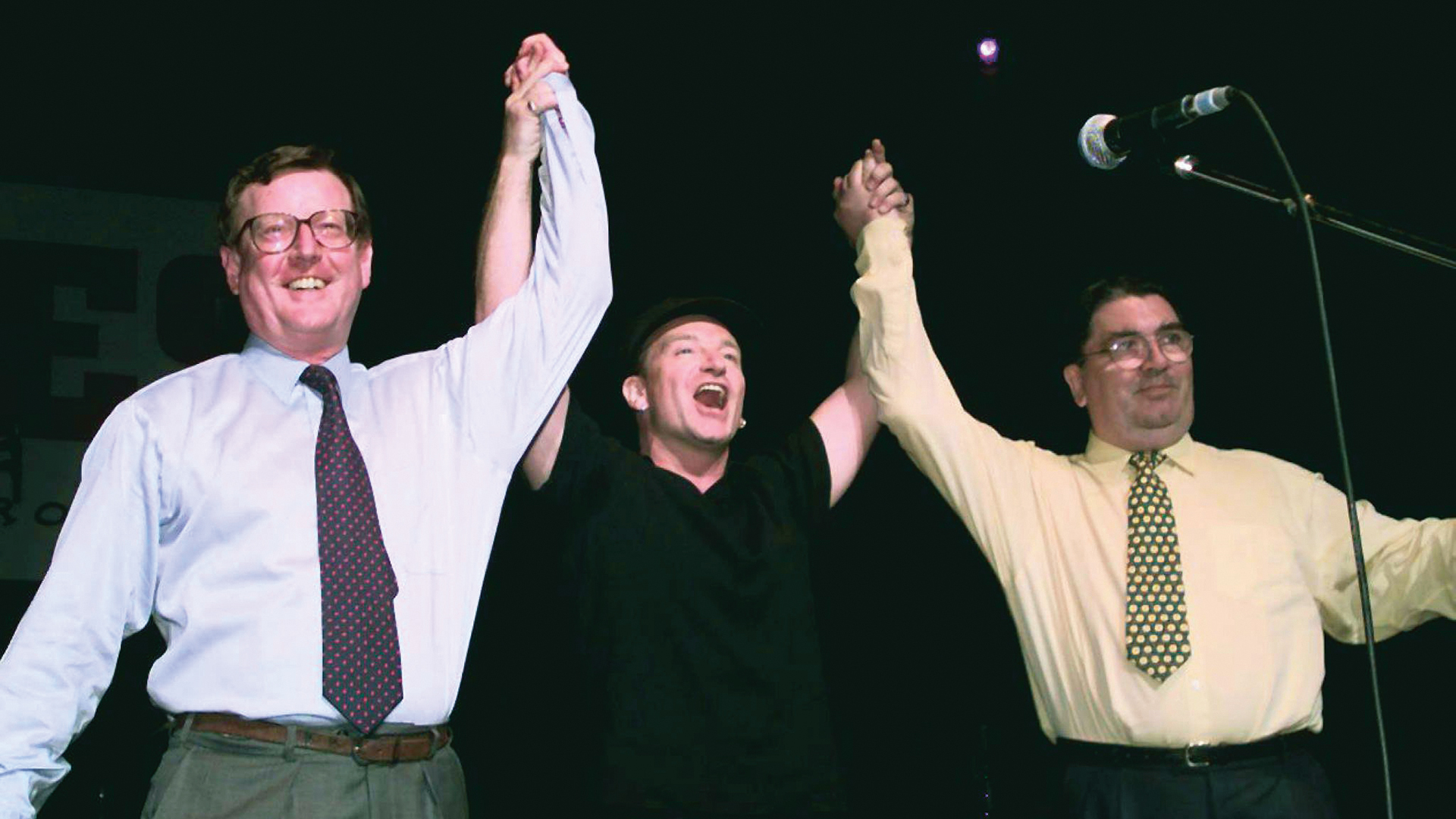

As President Biden, the Clintons and other VIPs head towards Belfast to mark the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, you could ask, what exactly is there to celebrate?

The much vaunted power-sharing government, which was meant to unite unionists and nationalists, is currently not functioning. Indeed the Stormont administration has been in some form of suspension for as many years as it has been up and running. Brexit ignited concerns about the land border with the Irish Republic, an area where tensions had previously abated due to a combination of joint Irish-British EU membership and the dismantling of the network of army frontier checkpoints and observation points which grew up during the Troubles. Dublin’s worst fears about the erection of a new “hard border” were assuaged by Boris Johnson’s agreement to a protocol designed to guarantee smooth north-south trade. However that protocol, despite Johnson’s denials, involved the creation of a new border in the Irish Sea, which hampered trade with Great Britain and stirred acute unionist anxiety over the perceived erosion of their British identity.

Away from the high politics, Northern Ireland continues to struggle with low wages, high levels of economic inactivity, hospital waiting lists which dwarf any other area of the UK and persistent pockets of deprivation. In some of those areas, paramilitary organisations still wield authority based on fear. In the weeks before the presidential visit, loyalist groups in Bangor and Newtownards threw petrol bombs at rivals’ homes in what appeared to be a feud over drug dealing and criminality. In Omagh, the police are hunting for dissident Irish republican gunmen who ambushed a senior officer, detective chief inspector John Caldwell, while he was putting footballs into his car boot after coaching a youth training session. The officer survived, but suffered life-changing injuries.

So on the political, economic and security fronts, it is far from a perfect peace. However the glass is half full, as well as half empty. The Belfast trade and investment advisers OCO Global recently produced an analysis which found that Northern Ireland’s Gross Domestic Product has more than doubled since the Good Friday Agreement, with average GDP per capita increasing from £13,391 to £25,575, one of the biggest improvements across the UK. Northern Ireland now has vibrant cyber security, financial technology and pharmaceutical sectors. Tourism has been fuelled not just by morbid curiosity about the Troubles, but also by a fascination with the culture of the new Northern Ireland. Besides photographing the Peace Walls, visitors want to see the filming locations for HBO’s Game of Thrones or Channel 4’s Derry Girls.

- The man who never gave up on peace in Northern Ireland

- Sian Brooke ‘fell in love with Belfast’ making gritty police drama Blue Lights

- Derry Girls: ‘What Lisa McGee has done is change the path for all Derry girls going forward’

More than this, the casualty graphs are clear. The Troubles as we knew them for three decades are over and hundreds of people are walking the streets today who might have fallen victim to political violence if there had been no agreement in 1998. However Northern Ireland still craves political stability. Rishi Sunak’s ‘Windsor Framework’ has taken some of the rough edges off Boris Johnson’s Protocol. The DUP may never accept the latest deal with the EU as good enough, but at some point unionism may have to decide this is “as good as it gets”. They won’t factor the Biden visit into that decision, but are likely to delay it beyond forthcoming council elections in May. Even if Stormont is revived, that won’t be the end of the story, as the challenges ahead are severe and the machinery of government created in 1998 is distinctly creaky. The glass is half empty, but with a degree of ingenuity and mutual trust, it can be topped up.

Mark Devenport is former BBC Northern Ireland political editor @markdevenport