That alas, is the lot of the place of my birth, born as I was up the road a few minutes from where Grenfell killed so many people. Knowing the slum streets that were blown up to make way for Grenfell I can’t help but feel that Grenfell is more symbolic (yet real) of a deeper malaise that dogs local democracy.

Nottingham has always had a great pull for me because it was the first place I ever recognised as representing a different Britain to the one I grew up in. I grew up in a slummy London that did not have Nottingham’s big factories and the row after row of poorly made housing. It had different people who spoke with what we in the South took to be northern accents, only later to discover that they were in fact Midlanders.

There was a closeness among industrial workers and their families and the areas they came from. And it was only when I moved north and lived for a few years in Yorkshire that I understood this, in those solidly industrial times before Thatcher’s new broom swept away the UK’s industrial solidarity.

But before I went north, in 1961 aged 15, I lined up to see a film that would blow me away. Set in Nottingham in and around the Raleigh bike-making factory, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning was the first truly powerful film I had ever seen, containing these exotic ‘northern’ people who drank hard, worked hard, fought hard and seemed to stick to each other in a way I had never experienced. My working-class life seemed to be full of thieves and wife beaters, full of people who did not bind together in the face of employers. Seemed in it just for themselves.

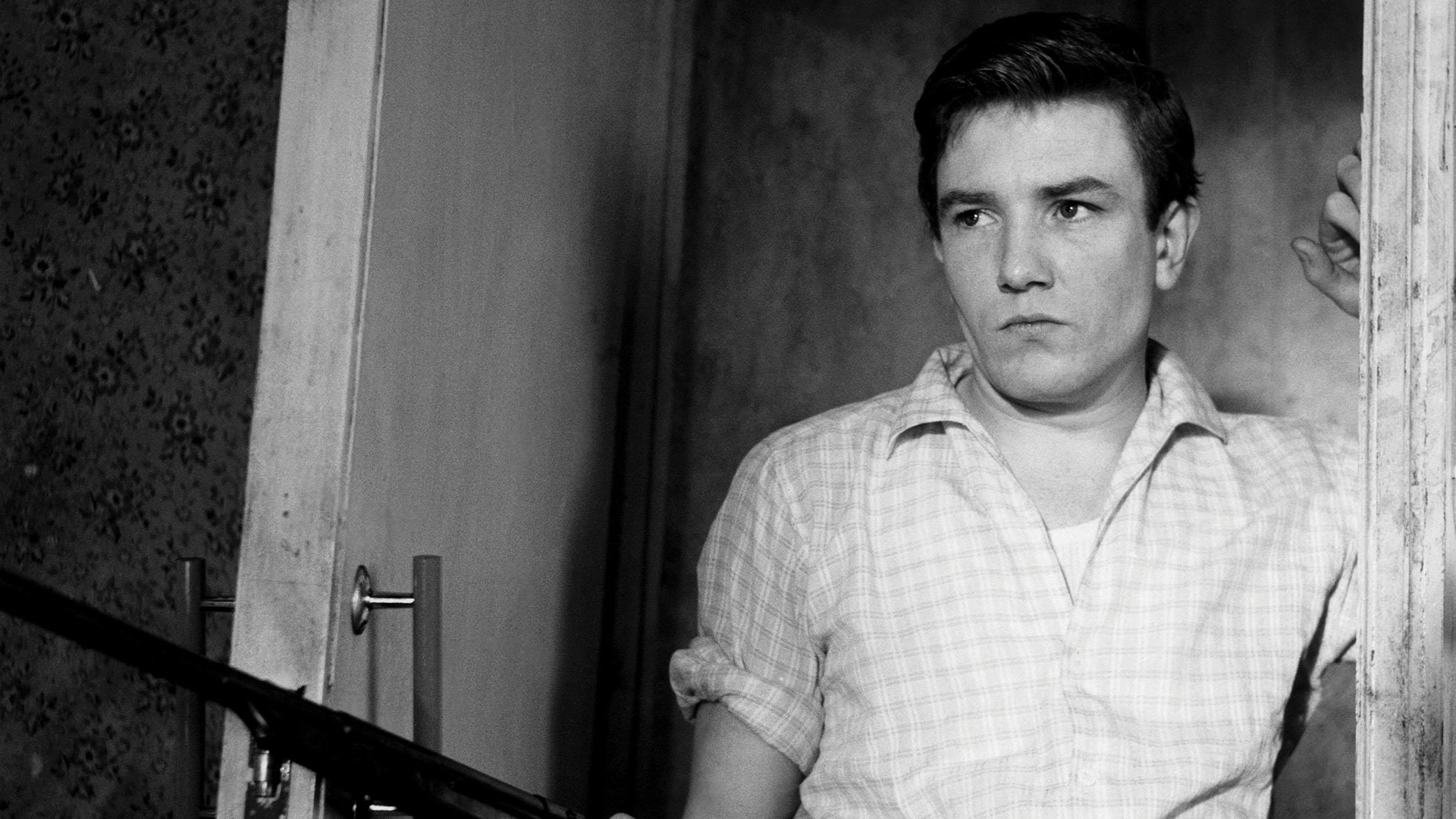

Albert Finney, the star of the film, was young, strong and handsome – and speaking the words of the great novelist Alan Sillitoe, a Nottingham man who wrote the book from which the film was made. This was an amazing and different world from my own working class, where the posse I moved around with seemed intent on harming each other – and anyone else who got in the way.

My canal walk through a former industrial landscape was a treasure, reminding me that at least once a year I would always advise people to get out and do things that were healthy and free. I would write a Big Issue article that celebrated casting off the ‘slough of despond’, as I believe Bunyan said, and getting on ‘Shanks’s pony’ (a reference to your feet) just to promenade wherever your fancy took you.

But in our cost of living crisis, and during Covid before, I seemed to have pulled in my advice to get out and saunter freely. Not wishing to be mistaken for a variation on Norman Tebbit, who once said to unemployed people, “Get on your bike.” In other words, if you’re without work try harder.

Another great Alan Sillitoe story, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, about a reformatory boy, was also turned into a film in 1962. Set in and around a youth offenders’ institution, it coincided with my own youthful incarceration and having to learn to run for miles cross country. I can remember the pain of running until you got your ‘second wind’. That was like suddenly realising you were rocket powered. I recommend it to anyone yet to discover the beauty of it.

I returned home southward, my nostalgia for the Midlands and the North still intact. It’s a great country up there. And University of Nottingham campus was a brilliant place to visit.

John Bird is the founder and editor-in-chief of The Big Issue. Read more of his words here.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? We want to hear from you. Get in touch and tell us more

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy!

If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue or give a gift subscription. You can also purchase one-off issues from The Big Issue Shop or The Big Issue app, available now from the App Store or Google Play